ASH IS PUREST WHITE

June 20, 2020

China is no doubt experiencing major socio-economic transformations at this moment in its history. These major changes may affect men and women differently. In China, as elsewhere, the balance between the two sexes may be changing.

Chinese film by Writer-Director Zhangke Jia, 2019. Drama/romance.

INTRODUCING THE STORY

(this is a spoiler alert: do not read this section if you wish to follow the plot only at the screening of the film)

In this most recent film presented by veteran and acclaimed director Zhangke Jia, the story revolves around Qiao, female companion of a local mafia boss named Bin. The film presents Qiao’s story, which starts in Datong, a run down and declining mining city of China, where she assists her Mafiosi husband in his various negotiations and responsibilities, working from an equally run down and non-descript semi-legal bar.

In the context of this economically challenged town, Qiao is the daughter of a laid-off worker, who laments the loss of his job. We can even hear his lamentations on the local radio station of this economically depressed environment, but to no avail. Not much can be done in the face of larger economic interests.

Qiaos’s companion (Bin) has his own worries, as he is involved in local Mafioso turf wars. At one point, he is attacked in his car by a dozen or so violent youths who are beating him up quite badly, until Qiao, taking the matter in her own hands to protect Bin, warns the violent youths that the next they will hear from her is through a gun she is waving at them.

The public authorities investigating the incident want to know where she got the gun, and to protect her companion from prosecution, she keeps that information for herself, fearing that that information could jeopardize the whole of Bin’s future. All of which results in five years of prison for her. Bin does not seem to go out of his way to help her.

After serving her prison term, she sets out to find Bin, and realizes he has not progressed much in her absence. In fact he now appears weak and diminished, psychologically and physically. In response to Bin’s lament that he has lost his compass, she replies that he « was », at one time, ,a mafia chief, but is no more.

Before locating Bin, her journey outside prison had brought her through large sections of China, to different location, using different transportation modes. In the process, she meets less than recommendable individuals, including a fellow passenger who steals her money and documents.

Her journey also leads her to the site of the transformation of the Yangtze River, with important water redirection, and where the giant Three Gorges dam is being constructed.

Qiao’s journey is also her own evolution, her personal trajectory, from a female companion of a local Mafioso boss to being her own woman, so to speak, complete with moral fortitude and even some undeniable wisdom.

Men around her are weakening all along. Her father lost his former status, as we have seen, and her male companion’s social slide downward parallels her own rise.

THE ELEPHANT BEHIND THE FILM

When looking at such a film, the unavoidable question is whether this tale says something, more generally, about contemporary China itself.

In the spirit of The Movie Shrink, we are unable to resist this temptation here.

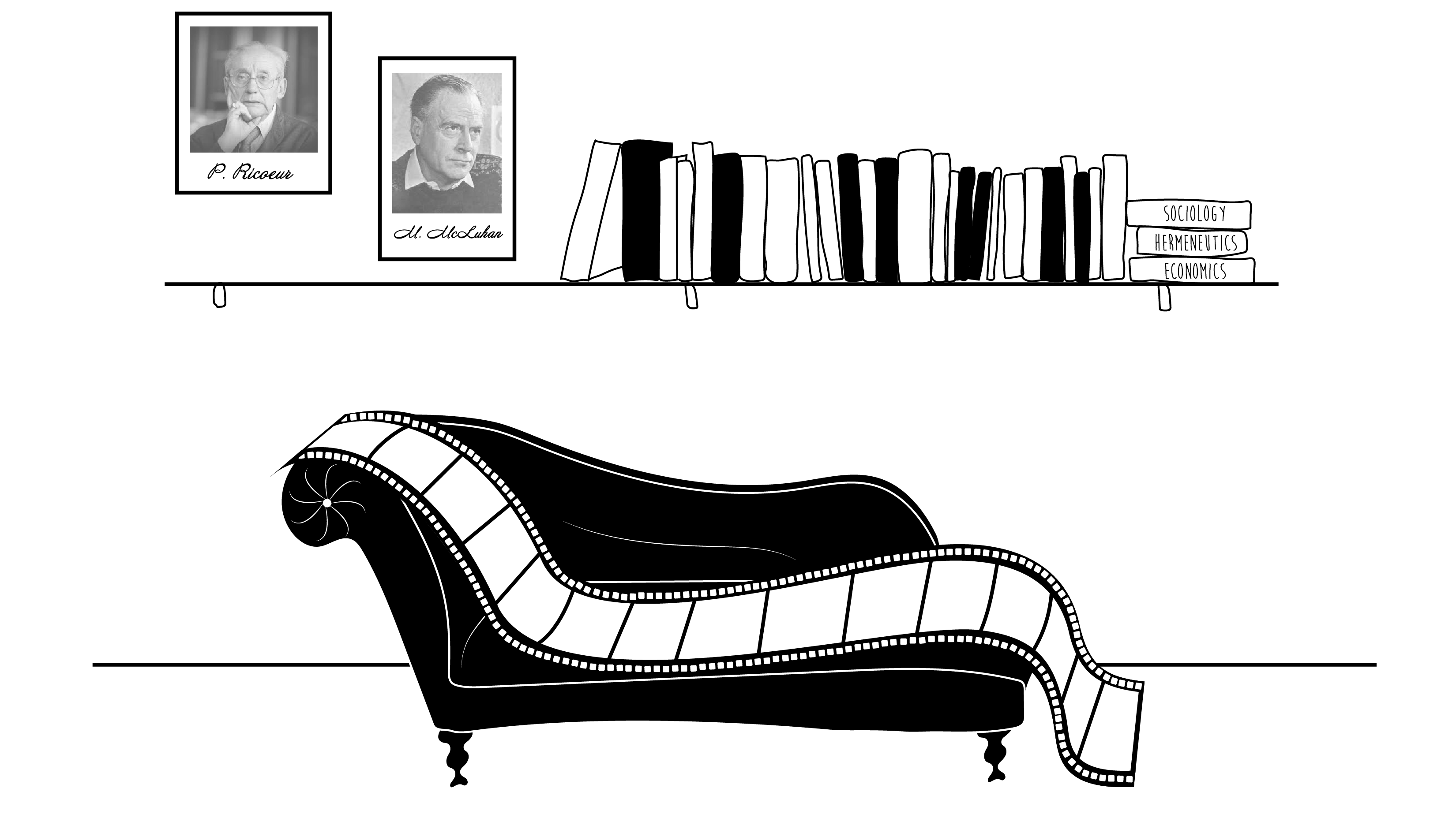

There is a large consensus that China is experiencing profound and large scale changes. But how these mutations affect individual lives is a question more difficult to identify and understand. This is where art and art work, and of course films, can provide what formal sociology and economics cannot.

And so, in this spirit, let us look more closely at some of the elements of Ash is purest white.

The film seems to suggest the possibility that men (as compared to women) may be particularly disoriented by the disconcerting mutations of modern China. Indeed men, even today, are still more involved in the work force, where these seismic changes are more directly felt. More specifically, rapid and important changes in the scale of organized life, from the local sphere, from which both Qiao’s father and her companion Bin drew their authority, to the larger, sometimes gigantic, contemporary projects of modern China, where a personal, concrete authority is more difficult to identify. Much is lost in these mutations, at least temporarily, and particularly for men in the work force (and that includes the mafia level of organization, like any organization). The dozen young men attacking veteran Mafioso Bin on the street are witnesses and participants to these changes of scale.

Reflecting on this film, and going apparently in the same direction as we propose here, Slant Magazine critic Sam C. Mac refers to a « profound statement on the spatial and temporal dissonances that inform life in 21th century China », creating a « national malaise » ( Peter Bradshaw, in The Guardian).

Many cross-currents of scale are presently at play in China. Many contradictory currents have indeed been referred to in order to describe contemporary China. Some point out to privatization, on the one hand, others to the continued large role of the State, on the other hand, heavily involved in large infrastructure construction, like the giant Three Gorges dam shown in the film. While privatization is no doubt on the move, it does not preclude the continued importance of large centralized government action, all of which contributes to the endless and inconclusive arguments for or against privatization , since a lot of partly contradictory cross-currents are happening at the same time. While there is the tendency to move out of centralized government and down to the operational level, the age old tradition of large government, best described by Karl Wittfogel in his classic Oriental Despotism, in which much of the centralization occurring historically in China was related to large water diversion projects, in the same spirit as the contemporary Three Gorges electricity facility, shown in the film, is still very present and pertinent.

Let us return to the film’s main character, companion of the deposed mafia leader Bin, and to the film’s Chinese title, quite different from the title in French (Les éternels) and also different from the title in English (Ash is purest white).

The title in Chinese, if we are to believe the literal translation, refers in part to the notion of Jianghu, made up of two words, river and lake, and , taken together, meaning wetlands and, sociologically, a period of uncertainty and of the suspension of normal rules and the arrival of a different and particular set of ethics. Wikipedia adds that these instances of Jianghu take on a particular importance in periods of uncertainty and trouble.

THE BIG PICTURE

The film’s story line suggests that women are less affected than men in this period of Jianghu.

Is that to say that, in China, as elsewhere, there is a swing towards more power to women, just as there is in films coming out of the West (The Favorite, Queen of Scots and many others) ? It is, after all, now, a global world, a global village.

In Ash is purest white, we are witness to this global trend, with a particular Chinese twist to it.

As the ecologists suggest: the more local, the more universal. It may be the case here.