WOMAN AT WAR

June 20, 2020

The state of the environment is a serious subject, and this film addresses that important challenge. But the light tone of the film leads us to believe that there is something else in this film.

Iceland, 2019, directed by Benedikt Erlingsson.

THE STORY

(this is a spoiler alert: do not read this section if you wish to follow the plot only at the screening of the film)

In contemporary Iceland, Halla, a local choir conductor by trade, is also, in her secret life, an environmental warrior, who spends her spare time attacking electricity pylons that are providing energy to an aluminum producing plant, related to a Chinese global company, very much immersed in global trade and environmental degradation.

The films follows her secret and sometimes comic ecological adventures of infrastructure destruction, from the planning phase to their implementation.

Halla is a bachelor of sorts, in her early forties, and she learns that a previous application to adopt a Ukrainian girl is now accepted. This causes some personal dilemmas, because her eventual accusation stemming from her unlawful activities would prevent her from being an acceptable parent for the adoption agency.

And, so, her secret ecological activities must be all the more secret.

But the police, as expected, is closing in on her activities, and on her. The police’s progress is entirely due to technical expertise, and not to any leaking of information, even though there is no absence of persons who could have denounced her. Her choir male friend, involved in his working life in government, at the highest level, does not reveal her activities. A farmer, whose operations are situated near her monkeywrenching and illegal activities, protects her from inquiring police patrols, and even lends her one of his vehicles for her to sneak out of his neighbouring pastures. In an incidental conversation with her, the rugged but aiding farmer had mentioned that they could be related, possibly as cousins.

Later in the film, towards its conclusion, after Halla is identified and arrested, her twin sister Asa, whose life project of her own was to reach her guru in India for an extended stay of spirituality, agrees to trick the authorities of the prison in changing place with Halla, since the prison would offer her the solitude and reflection opportunities that would have been possible in India, leaving Halla free to take custody of her new Ukrainian daughter after her tricky exit from prison and arrival in war stricken and somewhat disorganized Ukraine. Before this odd and somewhat spectacular exchange of prisoner, Halla had told her twin sister that she kept her activities out of her sister’s knowledge, in order to protect her from being also accused by the authorities.

THE ELEPHANT BEHIND THE FILM

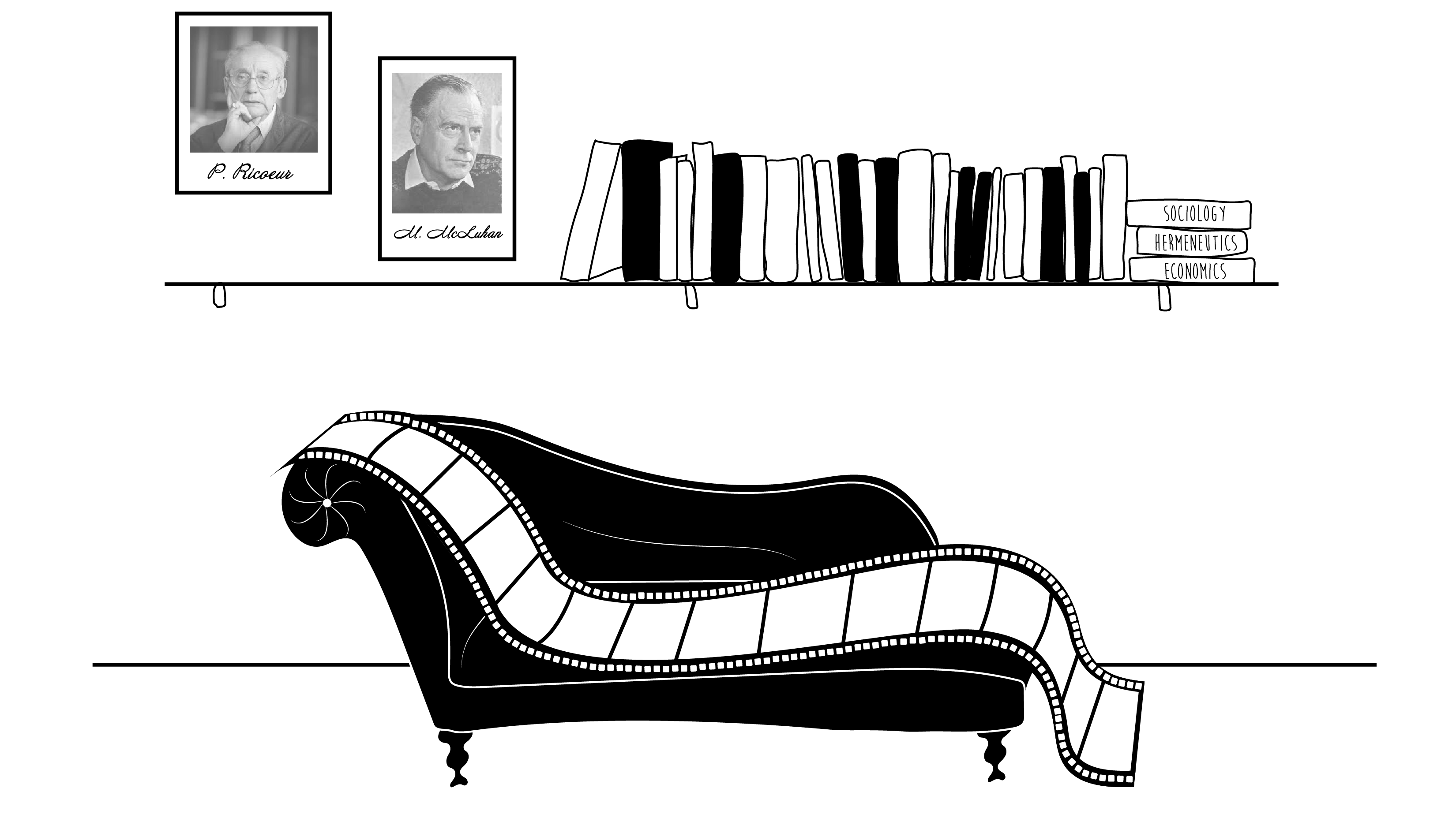

At first glance, this film is an ecological fable, presented however with a certain degree of humor. Often appearing on the screen is an intriguing musical trio providing a somewhat comical soundtrack and, later, another group, this time of Ukrainian folk dancers, also appears somewhat awkwardly, on the film set. This de- dramatizes the ecological struggle of the heroin. The ecological battle does not, consequently, appear to be so urgent or pressing, as these two artistic trios appear and disappear uninvited on the film set, providing some comical dimension to the whole story.

This comical element brings us to conclude that we may have to go beyond the ecological fable to grasp the essence of the film.

The film may indeed not be so much about the pressing environmental struggles as it is on the necessary underlying bases for these post-modern concerns. The elephant on the screen, which can be easily overlooked, like most elephants on the screen, that is to say too obvious to notice, may very well be the particularly harmonious social and human interactions between the characters of what seems to be an Icelandic social paradise. Halla’s role as a choir conductor, in search of harmony, seems to permeate all the characters of the film. For starters, as suggested earlier, the twin sisters are in harmony, to the point of adapting and modifying somewhat their life long goals in order to help one another; the government official keeps his secret to protect his friend Halla; the farmer shows great solidarity with Halla’s project, while not really knowing her at the start.

Overall, Iceland seems, from this point of view, a haven of human interaction.

THE BIG PICTURE

Through this evolving story, there is the underlying suggestion that ecological consciousness and goals could be more likely, at least at the outset, in societies that are themselves, socially speaking, harmonious and well-functioning, as though the pre-existing harmony can provide a model and an inspiration for the harmony for larger entities, planet earth and the global sphere, even reaching out to children in Ukraine.

But, of course, as we move from smaller entities to larger ones, harmony is more difficult to achieve: more difficult on planet earth or in Ukraine than between twin sisters or between citizens of a democratic and well -functioning country like Iceland.

On the ranking of total citizen welfare, Iceland is ahead of many countries that we would spontaneously think of at first glance, once public health and security is taken into consideration. Once one’s own house is in order, it is easier to start thinking about planet earth, which is why Europe (and particularly Northern Europe) is, generally speaking and all things considered, leading the way into ecological consciousness.

To fully understand the film and, relatedly, the process which brings post-modern concerns, we have to go back to Maslow and Herzberg’s theories about the hierarchy of needs. Taking individual humans as examples, the hierarchy of needs perspective states that it is only when basic human needs are satisfied (safety, food, clothing, shelter) that higher needs (the need for achievement, and self-realization for example) can be addressed.

As is often the case, it is through a comparative perspective that we can fully appreciate the film and the dynamics that brings about citizens from Iceland, in this film, to be particularly interested in improving the environment.

In quite recent films coming out or Iran, for example, films like Capaharnaum and The Client, it appears that some areas of the planet are so busy just surviving the difficult challenges of everyday human interaction that worrying about the state of the environment could be seen as a luxury.

But not in Iceland.