BULLET COMMENTS AUGUST 2020

August 4, 2020

The Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has had multiple effects on worldwide film production, distribution, and viewing.

The pandemic has had the short term effect of making some films more available for home viewing. It is not altogether clear yet if that will prove to be an enduring trend. The fact that this tendency was already emerging before the pandemic could indicate that it is a long term trend.

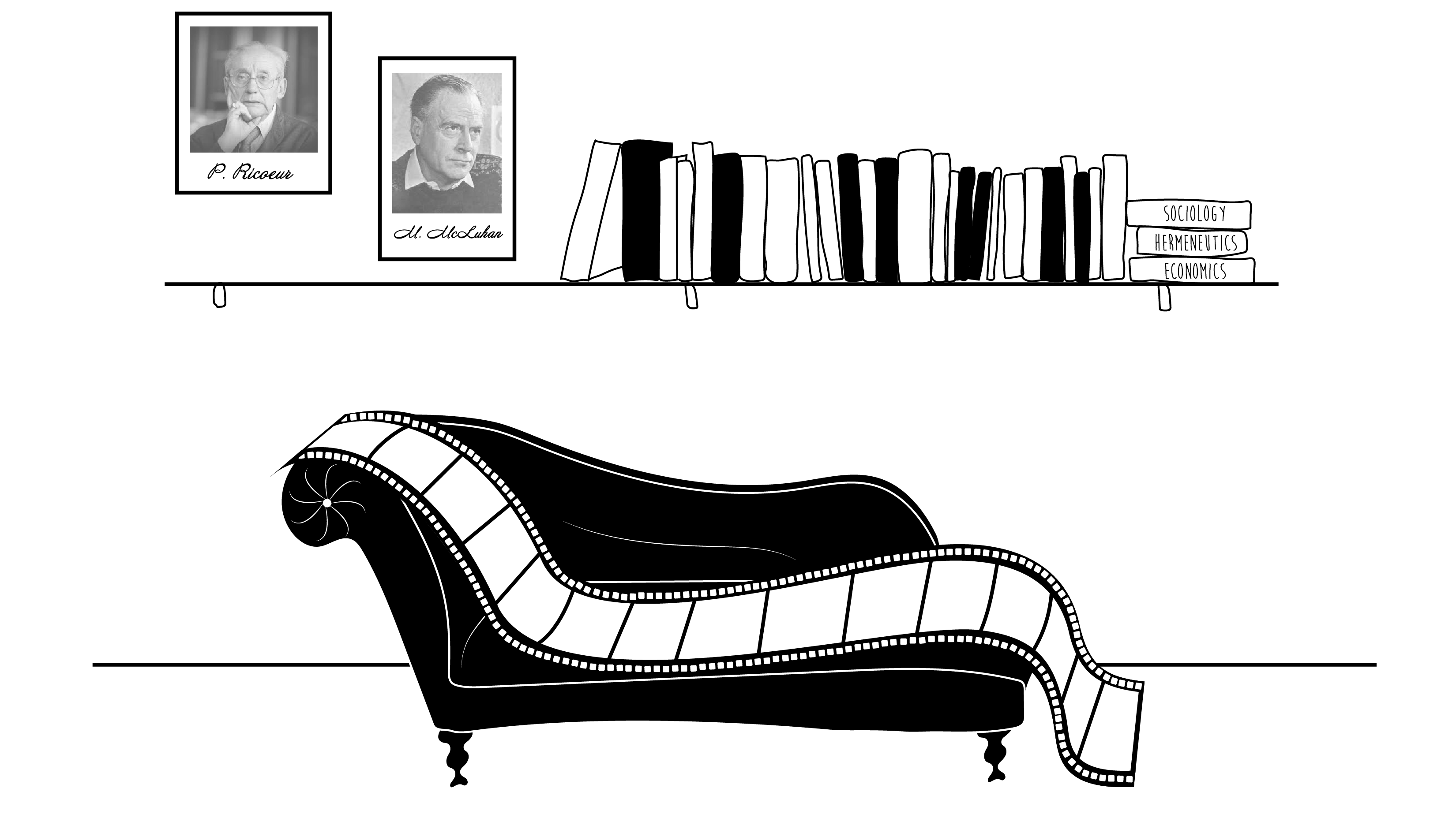

Before looking at general trends that go beyond particular films in this Bullet Comments section of The Movie Shrink site, let us say a few words about our goals in this section.

In other postings on this site, we pointed out that, to identify the films that we make somewhat extensive specific comments on, we must look at many other films for which we will make less extensive comments.

Some of these films could be amenable to hermeneutic understanding, but time constraints and other factors make it difficult to comment extensively on a large number of films. In addition, other films simply do not lend themselves to hermeneutic analysis.

Also, we want to avoid the following risk: If indeed, hermeneutics is everything, and can apply to anything, then it runs the risk of being nothing.

That having been said, here are, nevertheless, some limited and brief comments we can offer on a variety of relatively recent films. We are, in this case, interested in general trends more than in particular films. That being said, a few of the films briefly mentioned here may give way to more detailed analyses in the main feature section of The Movie Shrink.

Among the films of late 2018, 2019, and early 2020 for which we will offer our Bullet Comments, there will be films from North America and other parts of the world.

Looking at films of 2018, 2019 and 2020, The Movie Shrink can, indeed, identify several trends. We can distinguish between more difficult to identify trends and those that are more obvious.

In the first category of more difficult to identify trends, two trends stand out: first, the contemporary pressures coming from time constraints and media transformation, and, second, the dynamics of institutions.

Among the more obvious trends stands the age- old theme of the tension and relations between the haves and the have nots. This age-old and enduring theme in cinema offers particular twists in films of more recent years.

One of those twists concerns the theme of being black in America and, secondly, the more worldwide reassessment of the role of women.

So let us start with the more challenging to identify trends.

The first of these not so obvious trends is the question of time, or the pressures of time in contemporary societies, worldwide.

The first film to come to mind in this category is Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You (2019), a British-French-Belgian drama (which received numerous prizes), that chronicles the pressures, in terms of time especially, put on a British family where the husband is heavily involved in a corporate privatization scheme of parcel delivery services, under which he becomes financially responsible for the inevitable delays and problems encountered. The scheme is not as profitable as expected, not counting that it is destroying his family life.

Another dimension to this theme of time is presented in Hummingbird (2018), featured in our main feature section, a Canadian-Belgian drama that brings another angle to the pressures of time. These pressures are seen here from the side of the winners, where the main characters are planning a scheme to save time in stock market transactions to gain millions of dollars. But, here too, time is of the essence, because a rival plan could be operational before their own. It is, quite literally, a race against time.

Earlier, in 2016, a film out of Bulgaria, Glory, suggested that the problem of time, and time constraints, are universal. In this story, a Bulgarian trackman, after finding lost money on the railroad tracks, turns it over to the government, only to find himself become a media persona, deprived of his old and dependable watch (called Glory) in favor of a new but malfunctioning digital watch, by an unscrupulous media relations official, herself living from minute to minute under the dictates of her cellphone.

Related to this theme of the pressures of time is the theme of the changes in the media landscape, in this early first century of the millennium.

The Hunt, a horror-thriller American film of early 2020, does not leave much to be interpreted, as it only pushes further the existing cultural tensions in America, where cultural elites are seen here as hunting rednecks in a park, under the influence of media wars which started on the Internet.

Another American film, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (2020), featured in our main section, tells of a time where the media outlets were more benevolent, helpful and even sweet, as the kind and loving star of the children show classic of an earlier time, Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood, Fred Rogers, is anything but a revengeful and hateful participant on the Internet. The film suggests how far we have moved from these gentler times.

In our second category of films that are more challenging to understand stands the theme of institutions.

This theme of institutions might seem a little too abstract for films of fiction, but The Movie Shrink is convinced they are quite present, if only in an indirect way.

First Cow (2019), featured in our main section, can be seen as a film on the birth of an institutional framework under primitive conditions. The film is about the rough life in an Oregon settlement at the beginning of the nineteenth century, where the two principal characters steal from an administrative official the milk of a cow, the one and only cow of the settlement. In this film, the founding elements of institutional life are composed of a mixed bag of different and somewhat primitive elements: physical intimidation, fear, revenge, corporal punishment, self-administered justice, tempered by emerging public authorities and the basic rules of a market economy.

Even when institutions are settled and stable, they may hide some more primitive and unrecognized elements. Such is the case with Asghar Farhadi’s Everybody Knows (2018). The film revolves around the mother of all institutions, marriage. A marriage celebration in rural Spain turns out to be less of a celebration and more an unwelcomed opportunity to revisit some shaky foundations of the family involved. Under the varnish of institutions, there are dark secrets and hidden truths.

Another dimension of institutions is suggested in Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Haven (2019). The underlying dimension here is the suggestion that institutions, and institutional life, once established, have automaticity and permanence to them, to the point that they can, to a certain point, escape reality. This story turns around a Palestinian filmmaker who is looking for financing for his films in France and in the United States. He does not find the financing he wants, but he is witness to haute couture and chic that seems to awkwardly permeate all public life in Paris, while sirens and implicit violence was ever-present in the American city he visits. Suleiman is no kinder to his own Palestinian homeland, where the characters have well established and dysfunctional (and sometimes ridiculous) habits of their own. Institutional life, once established, is hard to change. We mechanically reproduce our institutions without questioning them.

Let us now turn to the more easily identifiable recent themes, which can be summed up by the notion of the relations between the haves and the have nots.

Two of the most celebrated films of recent years have touched upon that unavoidable theme. It is telling that both movies end up in violence, a testimony to the tensions between the haves and the have nots.

In Todd Phillips’ Joker (2019), this psychological thriller chronicles the fight of the main character, the Joker, a failed stand-up comic, against the wealthy. In Parasite (2019), there is a South-Korean twist to the tensions between the haves and the have nots. It is, first, the fact that the tensions between the wealthy family and the poor family are not accompanied by a cultural divide, as is the case in the United States, as evidenced in The Hunt. Quite the opposite, the two opposing families have much the same cultural underpinnings, witnessed by the fact that the poor one can almost seamlessly take the place of the rich one, and even take part in the education of their children. Another South-Korean trait is that, in Parasite, the economic inequalities are not so much between individuals as between families, which is a confirmation of political scientist-sociologist Francis Fukuyama’s view that, expressed in his classic book Trust (1995), Korea’s economic success was, at the outset, built on a combination of family and government institutions ( whereas Japan’s success was based on evolving feudalism).

The tensions between the haves and the have nots have recently witnessed some additional contemporary dimensions, most present in North America.

Indeed, in North America, there are two themes which have recently kept our attention: films on the experience of being black in America, on the one hand, and films about the rise of female consciousness, on the other hand.

In the case of the experience of being black in America, the films that look at this question are often quite straightforward and do not need much interpretation from The Movie Shrink. That is the case with The Green Book (2018), If Beale Street Could Speak (2018), Moonlight (2016) and Ma (2019). In the case of Get Out (2017), released earlier, there may be more implicit elements, which may need to be looked at. For example, the fact that blacks, in the home of the hero’s white sweetheart, are kidnapped to use their body parts, is very intriguing and demands a second look. The implicit message, the elephant behind the film, as it were, might be that blacks are, yes, integrated to American society, but they are integrated only in specialized roles, not of course as body parts literally, but in very specialized roles, as musicians and sports figures for example. The more recent Us (2019), from the same director, is more difficult to decipher, and we will try to do this work more extensively in our feature section. This episode of a black family attacked by another black family, exactly similar to itself, as they are vacationing in their summer home near the beach, is very intriguing. It is difficult to identify the elephant behind the film. But because white families face the same danger from white families similar to themselves, in the small vacation village, it seems appropriate to take away an exclusively black interpretation of the film. Does the concluding images of the attackers, black and white, holding hands to traverse America from coast to coast suggest that to find unity, we must first face our demons, our social tensions, tensions between haves and have nots? Possibly, but not entirely clear.

Still on films produced that speak to inequality, The Favorite (2018) and Mary, Queen of Scots (2018) both continue the rich vein of reassessing the role of women in society, a theme very present in recent years. A more recent aspect of this reassessment, present in both films, may be that the rivalry is less exclusively between men and women but now includes rivalry between women. That observation might not be welcomed by all, but it flows from some of the recent films on the subject. Whether that element is a sign of progress or of a retreat is not altogether clear.

With this, we conclude our August 4, 2020 entry in this section of Bullet Comments.