US

June 20, 2020

Following the great critical and popular success of Get Out, any film by Jordan Peele would lead us to believe that it deals with black integration (or lack of it) in American society. But, in this film, that theme is less obvious, and the movie may concern all those that are forgotten, those that are underground, white or black.

Suspense, written and directed by Jordan Peele. United States, 2019.

INTRODUCTION

With his previous film, the acclaimed Get Out, Jordan Peele had surpassed all expectations, succeeding with both the public and the critics.

With the more recent Us, the expectations were, as could be predicted, important. Not counting that, as the director confided in interviews, the financing was made more abundant this time around, and the shooting, accordingly, made easier.

THE STORY

(This is a spoiler alert: do not read this section if you wish to follow the plot only at the screening of the film)

The Wilsons, an affluent black family of four, including two teenagers or soon to be teenagers, comes to the Santa Cruz beach town for a summer vacation in the family summer home.

Everything seems normal enough. However, in the evening, a strange family stares towards them from the outside. Turns out they are exactly similar to the vacationing family, each of them facing the exact copy of him or her, as the invading family terrorizes the original one.

THE ELEPHANT BEHIND THE FILM

With the previous Get Out of Jordan Peele, there was an understandable urge to interpret that intriguing film. It very much seemed to be a story about the uneasy integration of blacks into mainstream America. Indeed, all in that film seemed smooth in the process of black integration , until the viewer realizes that, in that story, blacks were invited to a white residence in order, essentially, for them to provide body parts, suggesting that blacks were maybe, yes, integrated into mainstream America, but too often in very specialized and limited roles. One spontaneously thinks of artists and sports figures.

But the interpretation of Peele’s more recent piece, Us, is not as easily understandable as a storyline suggesting a subplot on the challenges of integration. If only because the neighbouring white family of the Wilsons’, also vacationing, faces the same type of challenge, that of defending themselves from an identical and violent family (in their case a white family, of course) of their own.

The film continues to show a total invasion of similar cases of strangely alike families invading the vacationing town, eventually forming a human chain across America, from west to east. The film had opened on intriguing remarks about our forgotten underground tunnels and constructions, still beneath us, such as underground and abandoned subway lines or other municipal or public infrastructures.

Is the invading families’ human chain related to the film’s reference to underground constructions of the opening of the film? These intriguing elements cry out for an understanding. The elephant behind the film is not as easily found here as it may have been for Peele’s previous and acclaimed film.

The interpretation of Get out as a story about some of the particularities of black integration does not, indeed, hold as much here.

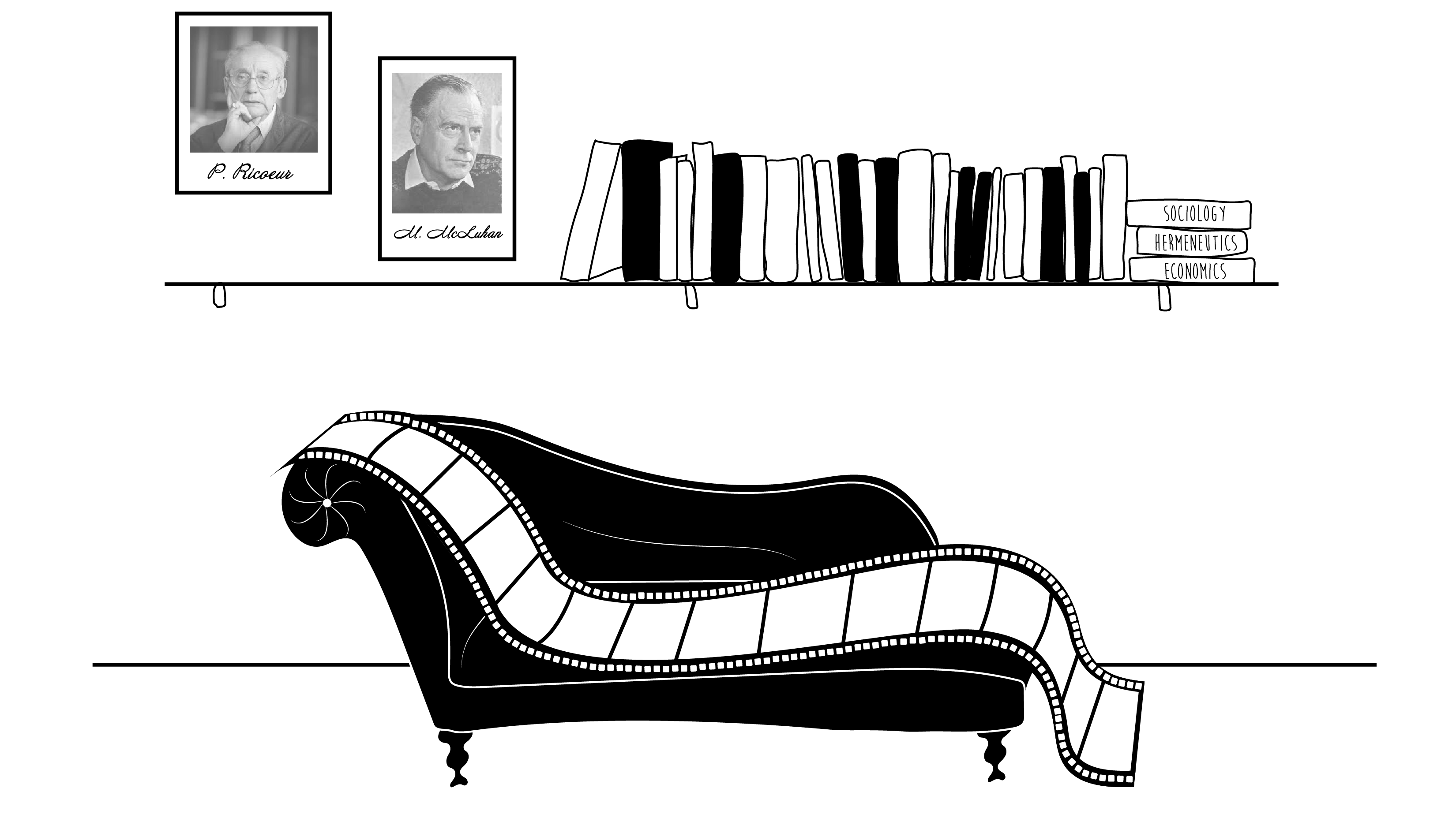

In our capsules about interpreting and understanding films, we argued that the films’ creator’s opinion about his intentions on his own film were not necessarily a sure guide to the understanding of the film, because the process of creation has an unconscious element to it, and because the creation of a true work of art escapes the intention of its author. In this case, however, it would be particularly interesting to know how Peel sees this particular film.

THE BIG PICTURE

Does a film, created by a black artist, necessarily reflect a black perspective? Or a film by a female director necessarily reflect a feminist perspective? After all, do we conclude that a film made by a white male director is a film proposing a story of white, male America? Not necessarily. On the other hand, films made by blacks and women, being still the exception than the rule in present circumstances, may be a special case, at this moment in history, and they may be particularly revealing of a particular perspective. And so, in a special way, Mary, Queen of Scots, The Favorite and Second Career are necessarily reflective of a feminist perspective and Moonlight, If Beale Street could speak and Get Out are necessarily reflective of a black perspective. There are tectonic movements below us and were are all feeling them, in one way or another, but some of us are better situated to reflect them.

Coming back to Us, the film may be alluding to all the have nots, the ones left behind, women, males, blacks and whites, who live underground, as it were, and who want to come out of obscurity and of darkness. They have been ignored, left underground, and with time, forgotten. Of course, they are mad, aggressive and dangerous. But dealing face to face with them will liberate both them, living underground, and us, living above. We are them, and they are us, but in different dimensions. « They » can indeed be different dimensions of Us.

Once they have come out of their underground, into the open, and recognized, then a human chain can unite us all, once we have each faced our demons, each different but strangely alike.