BULLET COMMENTS JUNE 2021

June 13, 2021

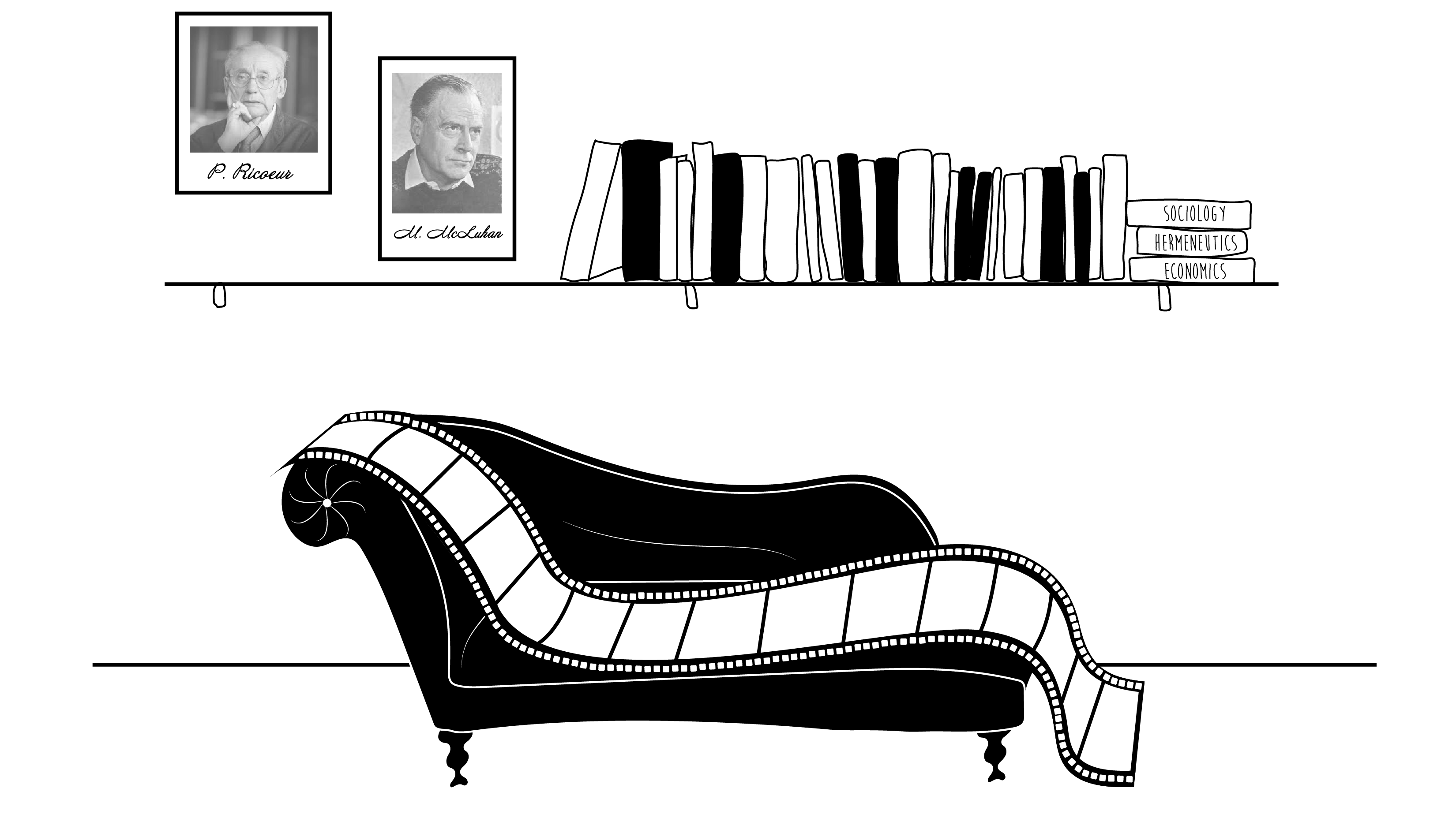

It has been a long time since The Movie Shrink’s last entry in our Bullet comments section.

We definitely have the intention of having more regular inputs in this section of our site, especially that a lot has occurred film-wise in the last few months, even with the pandemic slowing down filming, production, and releases of on-screen movies.

PRIZE-WINNING FILMS

Let us start with some of the recent Oscar nominations and winners that drew the attention of the film world and The Movie Shrink.

There have been especially two of the nominated films that seem particularly interesting. They are what can be called "social films", films about society that go beyond the individual story of the film. But these two films are not, however, militant, they do not want to denounce an injustice or cry out for some kind of reform. Films that are too militant often just turn us off, even if their topic is important and relevant.

Neither Nomadland nor Minari is a militant film, but they are socially relevant. Both films appear on our site in the main analysis section.

Let us start with Nomadland. With the risk of duplicating our feature analysis of the film that appears on our site, let us state however that one of the elements of the film is that it opens the door to several but complementing interpretations. The principal character of the film loses her job when the plant where she works closes, but her choice to then live in her van, working at odd jobs while touring the Midwest, is fueled also by personal preference. Through it all, there is however a main thread in the story, and that is the parallel between the main character's lifestyle, where place becomes irrelevant, and the type of service offered by firms such as Amazon (where she works part-time) for which place is not relevant either, other than as an element to be eliminated.

Minari would seem to be a less political, economic, or social film, and it is indeed less so. But as a film that tells us about a quite successful immigration story, it does speak indirectly to today's immigration in the United States, which has become a quite controversial subject, full of political heat. Just as A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (2019) does with our media environment, Minari makes us appreciate the gentle nature of previous times, not so long ago.

Sorry We Missed You (2019), a film not quite as recent, did not receive the same acclaim that the two previous films mentioned here, but it does address some important social, economic, and political themes, such as the personal perils of the gig economy, about the people who work without any security, sometimes worrying about where the next paycheck will come from. It is not a militant film, but it does point to contemporary challenges of the world of work and employment, and how it creates much anxiety, beyond the confines of the workplace. The film does not lead to a feature analysis in our main section, because it tells its story quite explicitly and directly.

THE STATE OF THE WORLD THROUGH FILMS

We often learn of what is going on in the rest of the world through newscasts telling us of a recent accident or political upheaval, leaving us often numb as to what has fuelled these events.

Then there are economic updates, telling us of aggregate statistical figures. They might speak to economists, but less so to those of us who are not too familiar with their implications.

What is going on in the inner workings of those places with which we are not very familiar? In The Movie Shrink's view, films can speak to some of those elements. Let us recall that, in The Movie Shrink's view of things, it is society that tells the story, as much as it is a particular director. Especially if there are recurring themes that mark films of different authors, creators, or directors.

What then transpires through recent films of different areas of the world, of different countries?

ASIA

Of course, the films from Asia we look at here are only a minuscule portion of films produced in Asia in a given year. There is, however, the possibility that films that find their way into the international scene may be more telling than most films produced in Asia. The Movie Shrink thinks this may be true, even though this notion might be somewhat self-serving.

Parasite, a 2019 acclaimed film from South Korea, is an interesting film that portrays a poor family imposing its presence on a richer one, through lies and tricks. The Movie Shrink, in a previous entry in this section, refers to Francis Fukuyama's idea, in his classic book *Trust (*1995), that the South Korean economic development owes much, at least in its beginnings, to the family structure as an economic entity. The story of the South Korean economic progress, in the past half-century, is in itself quite a story. Family businesses were a great basis for the first emergence of this success story, according to Fukuyama.

Parasite shows us how there is little cultural difference between poor and rich families in Korea, to the point the poorer one can replace the richer one, almost seamlessly. This says a lot about Korea, at least South Korea, but it also speaks to America, where cultural conflict would make this impossible. The Movie Shrink realizes that he is reaching into an Asian film to understand some of the recent American trends, but films sometimes lead us to surprising paths. Things have become very contentious in the American media and cultural scene. We are made even more conscious of this through....a South Korean film that speaks to the importance of the Korean family structure.

Ash is Purest White (2018) is another meaningful film from Asia, this time from China. Chinese films cannot ignore the huge socio-economical changes occurring in that fast-changing country. What Ash is Purest White tells us is that these seismic changes rearrange, among many sociological mutations, the roles between the sexes. That, of course, should not come as a surprise. The heroine's role is redefined and reassessed as her male counterparts have, comparatively, more challenges in finding their role in a new and evolving China. Women's roles are evolving almost everywhere, but with their particular local characteristics. This film speaks to those Chinese characteristics.

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

In the Russian film Taxi Blues (1990) of three decades ago, we had been given the impression that, from a socio-political perspective, things were not going well just before the fall of the Soviet economy. More recently, Beanpole (2019), set in post World War Two Russia, using the past to talk about the present, as so often is the case in films, gives a quite bleak image of what occurs in Russia. Human relations are strained and conflictual, and the décor is very much colored in grey.

Things do not seem much better now in the rest of Central and Eastern Europe, at least through the image given in films. In Glory (2016), a film that is looked at in more detail in The Movie Shrink's main section, a railway worker in Bulgaria is deprived of his faithful watch, Glory, when he is given in exchange a new high tech one that does not work. The film portrays the public relations officer who had initiated the change of watches, as a public relations move to draw attention away from the Ministry of Transport scandals, as someone who is dominated by her omnipresent cellphone. When both of these stories intersect, we are left with the impression that in Bulgaria, as in other Central and Eastern European countries, big economic changes bring about unsettling changes in basic elements of our lives, such as, in this case, time. Not an insignificant element, although not obvious at first glance.

The Whistlers (2019), set in Romania, tells the story of economic schemes, not legal, as the only sure way to find riches. When the schemers finally make it, they do not even spend their newly found riches in their home country. Many films from Central and Eastern Europe portray characters who seem to have the choice between being new losers or prosperous economic actors who have acquired their riches illegally, Russian style. The capitalist economy was so demonized during decades that the ones succeeding in it now locally can only be demons, according to this view of things. The situation also stems, in part, from a particular and excessively rough nature of the interpretations of what capitalism really is, an interpretation that permeated the Russian case in the early 1990 s, where so-called privatization was realized through quasi-theft of public assets, acquired at bargain prices.

WESTERN EUROPE

Mirroring their social and economic relative success, compared to other parts of the world, films from Europe nevertheless speak to some of the continent's particular challenges.

For many other areas of the world, the state of the environment is a concern, but rarely perceived in films of fiction as a pressing and immediate one.

In Woman at War, a film from Iceland (2018) looked at more extensively in The Movie Shrink's main features, is about an otherwise law-abiding citizen, who takes the law into her own hands to protect the state of her country's environment. Yet the film's tone is not at all dramatic, it is even somewhat comical. This leads us to believe that the film is not so much a militant piece about the environment. It may be a film about something else.

A slight detour is useful here.

Films are usually about challenges and difficulties facing societies. When these challenges are presented somewhat indirectly, as something to be discovered, they are of special interest to The Movie Shrink.

But what about films that portray, indirectly, something positive about a country, a culture? Is that still of interest for The Movie Shrink?

Case in point: the film Woman at War is supposed to be about environmental battles, and it is, partly. But only superficially. What transpires from the film, at every turn, is the harmonious nature of human and social interaction in that country, in Iceland. What can be concluded from the film is that concern about the environment starts with concerns with our fellow man. When a society is running pretty smoothly, it then can turn its attention to the protection of the planet.

Compare this harmony, portrayed at every turn of the film, with the strained human and social interactions presented in films of many other areas of the world, whether in the Middle East or in the developing world, whose economies are still struggling, and where interaction reflect these conditions. Even in Europe, a film like Everybody Knows (2018) (detailed analysis of it The Movie Shrink's main section), set in contemporary Spain, refers to the occasional conflictual nature of economic interactions, such as promises and contracts beneath the surface of economic life. The type of problem facing individuals in Everybody Knows is found more often in films coming out of the Middle East, in films of countries such as Iran.

Sometimes comparisons reveal common challenges, but sometimes very different ones.

This is why it is essential to see films from around the globe to get an idea of what is a topic of concern for specific countries or areas. Sometimes a film of a given country is explained in good part from films from another country or region.

Let us come back to Western European films, more specifically.

All things considered, Western European films, recently, have mirrored their own challenges. Some of these challenges are quite straightforward. But other films speak indirectly to challenges that are not so obvious. Subjects that can be seen as less grave or pressing can still be of concern.

The Scandinavian film Another Round (2020) tells the story of a group of high school teachers finding in scientific consumption of alcohol a source of greater well-being. As in Woman at War, the film we referred to earlier, the human and social interaction between characters in the film are quite harmonious, so there are no real challenges there. The film might be more about the fact that men, more so than women, can go overboard, so to speak, while concentrating on only one thing at a time, ignoring its interaction with other elements. Of course, this can be a problem, a challenge, but it can only be a concern when a lot of other problems have been attended to.

Such is the case with another European film, this time from France, Pupille (2018**)**, which speaks to the challenges of dealing with newborns who are left to public social services when biological parents feel unable to attend to them. Contrary to current public sector bashing, the film portrays the public servants in these tasks as quite considerate and even efficient. And so, the story that is told is as much a story of success as it is about challenges. Foster families are challenges of rich countries, of prosperous ones. Pupille is a film looked at in our main section.

The Movie Shrink does not look at documentary films, because of the fact they usually have a clear idea, a quite clear message, to convey. There is thus no need to interpret.

But while we are on the subject of France, a recent French film, partly documentary (as it is based on a true story, lived by the creator of the film) Au nom de la Terre (2019) (In the name of the land) says a lot about all the difficult changes that France has experienced in its move towards more industrialized agriculture. Pierre Muller has described these challenges in his 1984 book Le technocrate et le paysan (the technocrat and the farmer). Up until the 1950s, France's identity and culture were tied to small-scale, independent agriculture, and until then, it remained an important part of economic activities. The challenges involved in these changes are still working their way in the France of today, with the constant pressures coming from European and world competition. Consequently, because it deals with increased economic competition, it is a documentary about France, but also other areas of the world.

IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

Coming out of Africa, the film Night of Kings (2020) is set in an overcrowded African prison. It is a place you would not want to be. It is much like the Brazilian film of 2002, City of God, set in a favela. The merit of these two films, very much alike, is to tell quite frankly of the misery and enormous challenges of some areas of the world. Since the message is quite direct, The Movie Shrink has little to say about such films, they are almost documentary films. But they can be interpreted by comparing them to films of other countries, which address smaller and less pressing challenges, such as foster children or consumption of alcohol.

THE USA

There is so much cinema coming out of the USA that one wonders where to start. Keep in mind however that The Movie Shrink is interested above all in films that speak to challenges, in this case, American challenges, that are important but usually understated and alluded to, somewhat indirectly.

These constraints limit the number of films relevant for The Movie Shrink.

In the main section of The Movie Shrink, there are American films that are reviewed that remind us about gentler times in America. Two films in that vein stand out. First, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood remembers a time when our media were not so divisive, but kinder and gentler. It seems like a long time ago, before the war between CNN and Fox News, to give only one example.

Minari reminds us of a time when immigration was not a wedge issue, in the 1980s. So near in time, yet so far.

The Sound of Metal (2019), also viewed in more detail in our main section, seems to address a certain lack of equilibrium, the presence of excess in America. In that film, a hard rock drummer loses his hearing and tries to regain it. The fact the film ends in a quiet city environment in Belgium seems to tell us something, possibly alluding to the fact that older traditions are better prepared to integrate the new into the old.

This idea of a lack of equilibrium, of balance, may also be at play in films about America, such as The Dead Don't Die (2019) and The Hummingbird**Projec**t (2018), the first about the fact that people living in the same place are not really living in the same time zone, so to speak. The second one is about the improbable goal of connecting two distant American regions in the hope of cutting transmission time of stock market shares and profiting from it. In both those films, there is an absence of common sense, of equilibrium, of proportion, especially in the latter. Both those films are reviewed in* The Movie Shrink's* main section.

The particular theme of American films, at least those that caught the attention of The Movie Shrink, seems to address themes such as time, space, the influence of media in our lives and our senses. A film like The Vast of Night (2019) goes very much in that direction.

Because the United States is at the center of so many contemporary changes, some of these changes appear in American films but concern us all. We are all experiencing mutations in time, space and media, but the American adventure seems to be a place where these changes occur more dramatically, in a purer form, as it were.

The Movie Shrink is on the lookout for revealing American films, and he will take a look at recent films such as Limbo (2020), American Utopia (2020), Ammonite (2020), and The Truffle Hunters (2020) for more understanding of what American films tell us about contemporary themes and challenges.

The Movie Shrink makes a point at never criticizing films, and he is definitely not a film critic.

But exceptionally, he will offer some criticism here, and it will not be at all about the quality of a film. It has more to do with the idea that some American films refer in such a specialized manner to specifically American culture and film history that they almost exclude viewers from other parts of the World. Such is the case with Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019**)** and Mank (2020). To properly understand these two films, one must be extremely knowledgeable about American film history, and almost none of us is. Otherwise, these films do not make much sense. In other words, in contrast to most films of other countries (and that includes most American films), these films do not really intend to speak to a world audience, even though, because of their reputation, they might attract worldwide audiences. These films are, in a real sense, pretentious: they do not come to you, you have to go to them. They are the film version of "the ugly American".

The Movie Shrink is looking at the idea of presenting other socio-economic-political interpretations he finds elsewhere, and he wonders if our readers would like to know about them. Some film analysts and critics come close to what we try to do on our site. Would the occasional or regular inclusion of such other interpretations be of interest to readers?

More on that later, in the coming months.

For more up-to-date recent comments, please return to our Facebook pages. And for detailed comments on specific films, please go to our web site: themovieshrink.com

Thank you for your interest, and talk to you soon,

For more up to date comments, please go to our facebook page at facebook.com/The-Movie-Shrink. And for the analysis of specific films, return to our Home page.