EVERYBODY KNOWS

June 20, 2020

A marriage celebration is of course a joyous occasion. But in this film, the celebration brings back memories of events and transactions that the participants would have preferred to forget.

A film of 2018, by Asghar Farhadi. Spain- France- Italy. With Penelope Cruz (as Laura) and Javier Bardem (as Paco).

INTRODUCTION

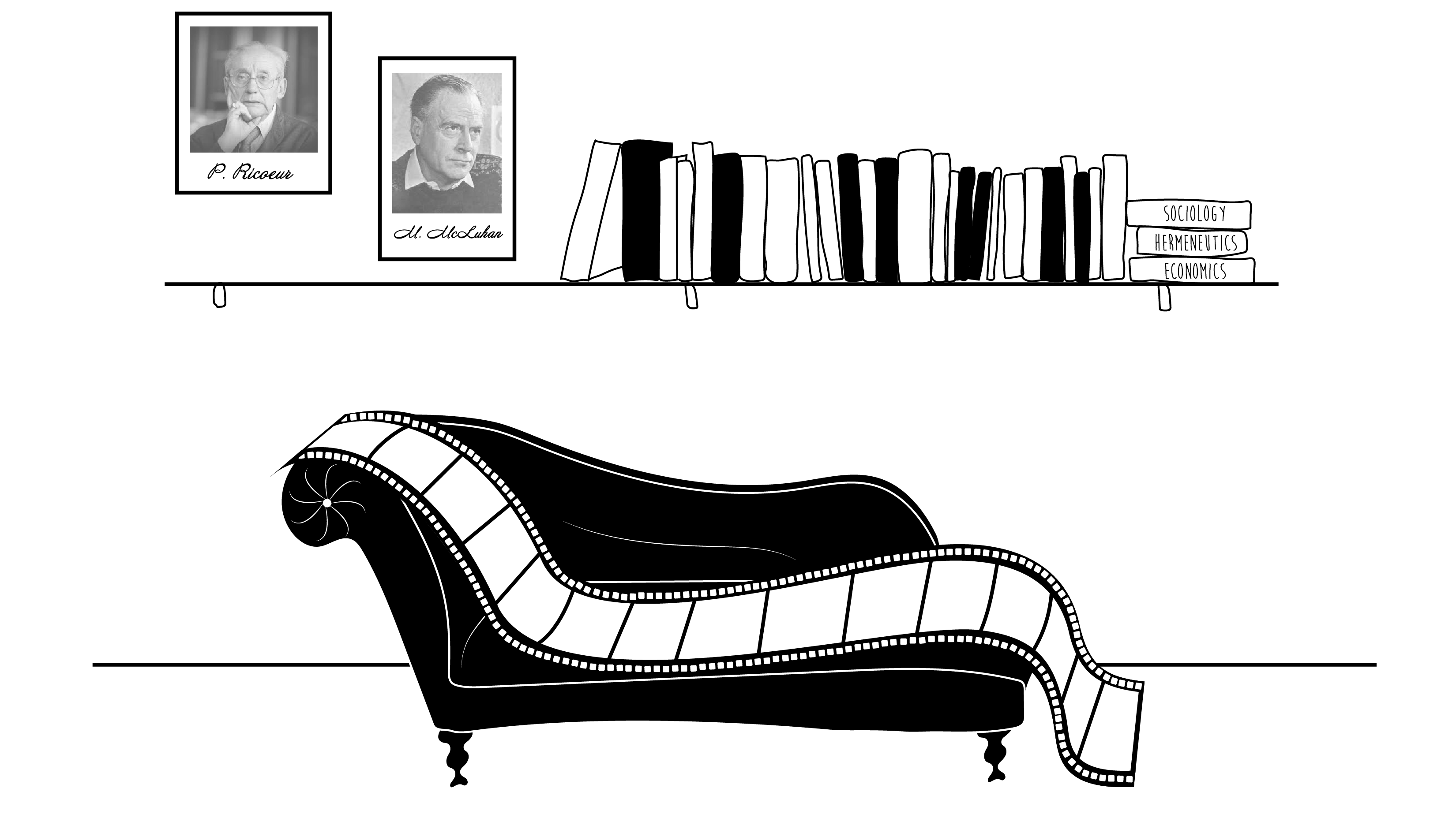

One of German philospher Hans-Georg Gadamer’s significant legacies was to show that art, cinema in our case here, is an important tool to increase our knowledge about society. This is surely the case with Everybody knows, a Spanish-French-Italian film released in late 2018.

In Everybody knows, film director Asghar Farhadi (with a proven track record of two Oscars, among other prizes), tells of the unexpected series of events surrounding a marriage celebration in Spain.

THE STORY

(this is a spoiler alert : do not read this section if you wish to follow the plot only at the screening of the film).

The story centers on Laura, a sister of the bride to be. Laura now lives in Argentina with a reputedly rich husband ( Alejandro), and she has made the trip to the small Spanish village of her youth for her sister’s wedding, with her two children ( a young son and a soon to be teenager daughter), as her husband stays home in Argentina because of pressing business appointments.

Among the other guests attending is Paco, Laura’s former sweetheart, who is now married and a prosperous landowner and wine producer.

The wedding celebrations, reminding the viewer of the opening scenes of the marriage celebrations in Godfather I, seems to be going fine. But amid the partying, Laura’s daughter is kidnapped from her room. A ransom is asked by the raptors through smart phone messages.

In the following events, all that seemed so perfect before and during the start of the wedding celebrations is put into question. A retired police investigator, called to investigate by a family member, concludes on an inside job, which puts into question the authenticity of the family ties. Laura’s husband, the supposedly rich businessman from Argentina, turns out, under scrutiny, to be ruined back home, and he (Alejandro) has been in reality looking for work for the last two years. But suspicion on him, to have in fact kidnapped his own daughter for financial gain, turns out to be unfounded.

Paco, the wealthy wine grower and former Laura sweetheart, the mother of the kidnapped girl, turns out to be the one in charge of the crisis, a role he will only accentuate once he finds out what Everybody knows, which is that he is the true biological father of the kidnapped girl.

Turns out that when the sweethearts broke up, about twelve years ago, Laura needed money and, to get some, she sold to her soon to be estranged sweetheart Paco some land, the land that made him eventually prosperous. The family had always resented that deal. One of Lara’s sisters’ husband turns out to be the kidnapper behind the drama. It is Paco who pays the ransom money, in effect paying back a family member the value of the land he may have gained originally from duress.

The teenage daughter is then released and the family of the married daughter is left with the task of settling the case of the family in law culprit, who was in fact acting without the knowledge or the blessing of the family.

THE ELEPHANT BEHIND THE FILM

It is not the first time that film director Asghar Farhadi deals with the strains of interpersonal dealings that have an economic dimension to them, as in The Client (2016), for example. But these challenging financial tensions were set in his native Iran. In this case, in Everybody knows, the setting is contemporary and relatively prosperous Spain. Yet the underlying themes seem to be, in many ways, the same.

In the case of the Spanish setting, under the varnish of apparently harmonious and prosperous social and economic life, there are many underlying strains. There are dark secrets, hidden grievances, lies and questionable bases and suspect dealings behind apparently normal and legitimate prosperity.

THE BIG PICTURE

Are these shaky bases and possibly immoral situations more prevalent, or somehow different, in some societies than in others? Would this be reflected in the films of specific countries?

Coming from the less developed world, and reflecting their own harsh economic realities, we can often notice these types of themes in films coming out of South America ( films recounting the insurance frauds coming from fake accidents, for example) or from Russia (Taxi Blues, a film on the disappointments and tensions vis-à-vis slow economic progress). Harsh individual circumstances are in such cases intertwined with economic difficulties. Our tunnel visions of studies of social reality, organized as they are in compartmentalized subject areas, in universities for example, do not often look at socio-economic realities and individual stories, taken together, but films and novels can. This is what is done in Everybody knows. And, so, as Daniel Bertaux observed regarding his own work in sociology, « people know or at least feel that their curiosity about social life will not be (totally) satisfied by (a specialized domain), and we should acknowledge that film-makers do more to bring contemporary society to an awareness of itself than anyone else » (1).

So the elephant behind this film appears to be the inherent and often dramatic challenges of humans dealing with one another, especially when there is a financial and economic dimension. Specialists coming from Institutional economics would describe these challenges as « transactions costs », a term appearing as early as the late 1930’s, referring to the cost and inherent challenges of doing business and entertaining economic relations with one another.

Was Farhadi’s intention to give a course on Institutional economics? Surely not. The deeper question here is: what are some of the underlying human elements beneath the surface of economic transactions?

And, still more profoundly, what are institutions, starting with this most enduring and important institution, marriage and partnering? It may be revealing that the film opens with the preparation and celebrations of a marriage, the mother of all institutions.

However imperfect, our institutions are all we have to regulate our economic dealings with one another. They are, in addition, the bases for all public life.

In commenting on the difficulties of specific countries in achieving democratic processes, we often identify the underlying cause as “political”.

But the bigger picture could point to a still larger cause: difficulties in dealing in everyday economic and social interactions, the big picture, the elephant behind the screen.

(1) Daniel Bertaux, « From the life-history approach to the transformation of sociological practice », Biography and Society, Sage, Beverly Hills, California, 1981, p. 29-46, p. 42.