FILMS OF 2020-2021 BY CONTINENT, REGION, COUNTRY

December 10, 2021

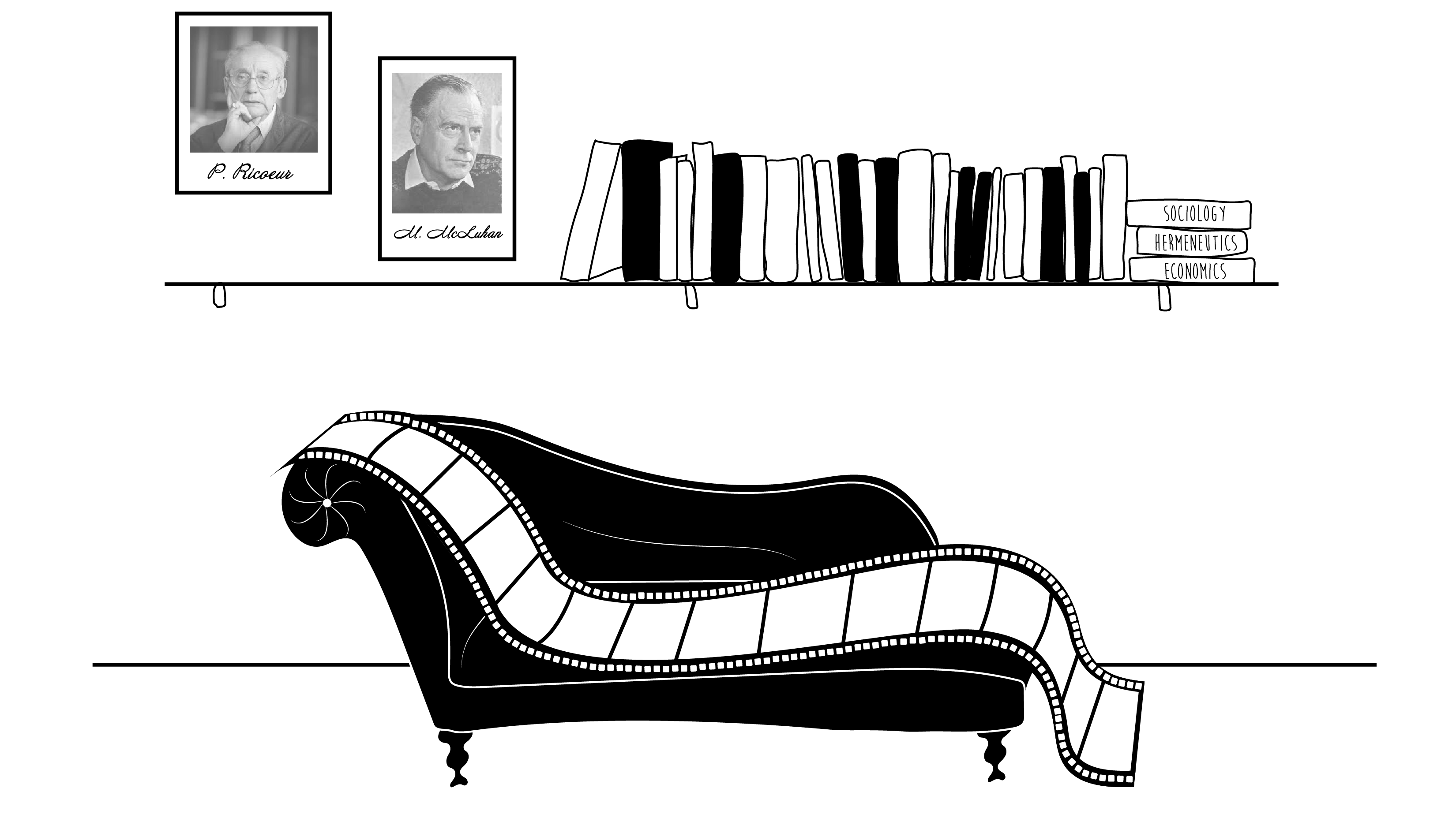

Do films have the same themes all over the world? Or do they treat subjects that are particular to their own experience? Let us try to answer here, in part, those questions.

Identifying trends, according to continents, region, or country, requires sometimes that we look at films over several years, and that is why, even if this review will focus on films of 2020-2021, we will sometimes look at films that are less recent, such as films of 2018-2019, to better understand them.

Let us also point out that films can sometimes be looked at as a cluster of films that somehow relate to each other. One can find such a case with the theme of the death or disappearance of young children, a theme that is particularly present in recent European films, a theme that is difficult to understand or interpret, but that is nevertheless quite obvious in Western European films of 2019-2021. We will come back to this point later.

In a very general way, we can say that films from different continents, regions, or countries seem to correspond, at least partly, to an established idea in social and organizational studies, proposed by Abraham Maslow, and that is that there is a hierarchy of needs in human beings, whereby there are certain types of needs that drive us, according to different circumstances. In short, the idea is that humans are first motivated by meeting basic needs, of shelter, security, and food, and that it is only when those needs are met that we can turn our attention to other, less immediate needs, such as the need for sociability and self-actualization. These needs are universal, but they can be experienced differently in different contexts.

It is through this light that we can look at recent Western European films, for example, and, as we shall see later, we can see that several of these films have as central elements themes that go beyond pressing and immediate survival needs, as they are related to themes such as the preservation of the environment as in Woman at War (2018) from Iceland, or excessive alcohol consumption, such as in the Scandinavian film Another Round (2020). Compare these themes with films coming out of Africa or Eastern Europe, more preoccupied with questions of immediate socio-economic survival, such as This is not a Burial, this is a resurrection (2019-2020), set in Africa, or a film on survival in refugee camps in Bosnia, such as in Quo Vadis Aïda? (2020), or then again on pressing economic lifestyle choices, such as in the Romanian film Acasia my Home (2020-2021), depicting the difficult choices of economic survival in contemporary Bucarest suburbs.

In this film review of films of 2020-2021, we will sometimes be guided by this idea of the hierarchy of needs, from Abraham Maslow, and we will first look at films coming out of continents or regions which seem to be more preoccupied with needs that are more immediate and pressing.

With this in mind, let us begin with some films from Africa

FILMS FROM AFRICA

We have only seen a few films coming out of Africa, so it is difficult to see real trends. So we will look at two films that have brought attention outside of Africa.

Let us come back to This is not a Burial, it is a resurrection (2019-2020), a film that is often listed as one of the best films of 2020. It concerns the plight of a part of Africa that is forgotten by the economic advances of globalization processes. In a certain way, the film could be a film on many regions of the world that are forgotten by change and economic mutations.

There is a certain tradition in films out of Africa that describes very bleak circumstances, such as in the recent Night of Kings (2020-2021) that describes the everyday perils of surviving in an African prison. The film is reminiscent of a Brazilian film in the same style, The City of God (2006), on the perils of living in an atmosphere of the extreme violence of favelas we can find in Rio de Janeiro for example.

FILMS FROM THE MIDDLE EAST AND THE ARAB WORLD

Here again, it is difficult to draw specific conclusions from a relatively small number of films we have seen from the Middle East and the Arab world. Nevertheless, there is one film in particular that has made several lists of the best worldwide films of 2020-2021, the Iranian film There is no Evil (2020-2021), a film essentially about young men performing their military service and ordered to participate in executions, sometimes political executions. This military duty conflicts with their values, which leads to personal crises. We draw our attention to this film partly because, beyond its enthusiastic reception worldwide, it deals with closely related themes of other recent Iranian films.

This is the theme of the challenges of interpersonal relations, which are often ethical challenges. This theme is related, in There is no Evil, to the excesses of the regime, but then leading to challenges in interpersonal relationships. But the challenges of interpersonal relations, whether related to the regime or not, are quite present in themselves in Iranian films. These challenges are often related to economic exchanges. In well-known and acclaimed Iranian films such as The Salesman (2016) and A separation (2011), there are interpersonal conflicts that are tied to economic conflicts, such as contracts, promises to deliver in selling, buying, or renting, which in turn lead to interpersonal conflicts. In a film he directed in the context of a small town in Spain, Everybody Knows (2018), Iranian film director Ashghar Farahdi dealt with much the same patterns, a film whose story originates from a questionable transaction, a sale of sizeable real estate in the context of a couple preparing to divorce.

Coming back to specifically Iranian films, we can attribute the contractual challenges to the dynamics of an authoritarian regime, but the Iranian films seem to underscore these types of challenges in themselves, whether related to the political regime or not.

IN LATIN AMERICA

The somber experiences of the military regimes of the last century continue to haunt the memory of Latin America, and that is the case with the film about its Guatemalan version, in La Llorona (2019-2020), a film presented at the Toronto Film Festival. It is a film about grief and a kind of effort at reconciliation, in memory of the tragic events coming out of Guatemala, under the military regime.

In a more general context, quite apart from the excesses of the military regimes, Latin American elites continue to deceive and lie, at least in the themes we can find in films from that part of the world. The film Heroic Losers (2020-2021), a humor-filled drama set in contemporary Argentina, is about how unscrupulous bankers and lawyers conspire to deprive honest citizens of a small town and their dream to improve their economic lot.

An even more tragic outcome of theft and deceit from the authorities is reserved for citizens of a small and forgotten rural outpost in the acclaimed Brazilian film Bacurau (2019), where citizens are first deprived of access to water by the authorities, only to be hunted down later by a group of visiting tourists, with the possible connivance of a local corrupt politician, running for office and offering a young prostitute as a campaign promise.

The Columbian film We will be Forgotten (2021), is the story is about a compassionate physician trying to alleviate human suffering from a context of violence and drug trafficking, where the authorities are often incapable intervene or even, in the worst cases, participants.

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

The bleak and pessimistic view that is often given by films from Latin America and the Middle East also find their way into films from Central and Eastern Europe, but, of course, with a particular twist.

Of course, the whole world applauded the economic and political integration of countries from the former communist European bloc into the Western mold. Of course, this integration is seen as real progress. But these advances can also have their challenges.

We were alerted to these challenges in the Bulgarian-Greek film Glory (2016), in which an honest and peaceful railman is deprived of his old watch, given to him by his father, taken from him in exchange for a super-modern watch….that does not work properly. In The Whistlers (2019), the money gained illegally in an emerging market economy can only be spent in Western Europe, as it could draw the attention of authorities and criminals if it was spent in the home country of Eastern Europe. In Collective (2021), corruption can also be found in more traditional sectors of the economy, as it is in this film from Romania. It is a type of corruption different from that found in the communist era, but corruption nevertheless.

In another Romanian story, a documentary we have referred to above, Acasia my Home (2020-2021), tells of the difficult choices a family faces when confronted with a choice between living in a kind of controlled autarky and the uncertainties of the regular, market economy.

Some parts of Eastern and Central Europe are the site where refugee camps are set, and where individuals await their entry into Western Europe, as in the film Quo Vadis Aïda? (2021), a film out of Bosnia, which has been recognized as one of the best films from the world for 2021.

We have known for several years, if not decades, ever since the classic Russian Taxi Blues (1990), that the Russian cinema throws a dim light on current life in Russia, at least for the majority of people. Recent films show much the same pessimistic image, even if they use history to do so, as in Beanpole (2019).

There are of course many differing opinions as to Russia’s recent progress or lack thereof, but it is quite clear that recent Russian films give a dark image of life there at the moment.

FILMS FROM ASIA

Here again, we will base our first impressions only on a limited number of films. There are a great number of films produced in India any given year, for example, but, as in other cases, we will only look at some of those that gain attention from outside the country they are produced in.

In the specific case of India, the current film that has attracted attention outside the country is The Disciple (2020). Of course, there are pressing needs linked to challenges of immediate survival in India, but this film is more about less pressing needs, such as cultural challenges in the front of the assault of worldwide music and arts coming from the international market.

The acclaimed Korean film Parasite (2019) was more about class conflict than about immediate survival challenges, but it did have an economic dimension to it.

In the Chinese film, Ash is Purest White (2018-2019), the story is less about immediate economic survival as it is about the huge changes China is experiencing, from a generational and genre perspective.

FILMS FROM WESTERN EUROPE

What is striking about recent films from Western Europe is that they seem to tell the story of less pressing problems than most of the other areas of the world, even compared to the Asian films we looked at. If we look at this trend in the light of Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, described earlier, we can observe that they deal with topics that are less pressing than elsewhere.

That is not to say that all is easily resolved.

Of course, environmental challenges are important, and even grave, but they do not constitute imminent and immediate dangers in most cases. The film Woman at War (2018), from Iceland, deals with environmental challenges, but in a genre that is not too far from comedy. It is much the same tone with Another Round (2020), a Scandinavian film that depicts the quest of schoolteachers for additional well-being from the steadier consumption of alcohol, and it is set in a somewhat humoristic style.

Other challenges face rich countries, among them an unbalanced demographic situation, coming from a growing population of seniors, a challenge well known for Japan, but also present elsewhere. The British film The Father (2021) attacks this subject quite directly, with little need to interpret.

There is another social trend in more prosperous societies, and that is the proportion of “homes” that are occupied by single persons. As such, it is not a problem, and it is treated in a humoristic style in the Spanish film Rosa’s wedding (2020-2021). In that film, the heroine, Rosa, is organizing a marriage ceremony that will celebrate her marriage to…..herself.

The French film France (2021) – France can be a forename or Christian name in French-, gives us a portrait of a TV news star from Paris, set under mediatic turmoil. While the mediatic frenzy can create its own set of problems, we cannot describe them as immediate or grave problems that can endanger individual survival.

Of course, the winner of the prestigious Palme d’Or at Cannes’ Festival of 2021, Titane can be seen as defying interpretation, even possibly understanding, but its theme of genre modification and sexual transformation is not a pressing social issue of life and death, at least for most people, in Europe or elsewhere.

There remains here a question that may be, or may not be, significant.

It concerns the theme, in several European films, of the early death or disappearance of young children. These stories do not concern children that may have suffered traumatic sexual experiences, but simply children who died or disappeared for different other reasons. It is the case with the Scandinavian film Koko-Di Koko-Da (2019), with the Islandic film Lamb (2021), with the French-British film My Zoe (2021) and also the French film referred to above, Titane (2021), that is the story, especially in the second half, about a missing boy in France. It must be said, however, that this theme is also present, but less obvious, in the American film Land (2021).

It is difficult to say if this theme is accidental or whether it is meaningful, but it is too important to be ignored altogether, at least at the moment.

THEMES OF AMERICAN FILMS

There are so many American films to choose from that it is quite a challenge to find distinctive trends in any given year. This holds for the American films of 2020-2021, as a large number of different themes are present.

The year 2020 was a remarkable year, with several significant films. Nomadland was certainly one of the most significant ones, a film on the extreme lifestyle mobility of the heroine, a woman who worked part-time for an Amazon-type employer, a powerful film on our present economic environment. Living in one’s car, an emerging American trend, could be a kind of forerunner of lifestyles to be experienced later by other areas of the world, even if that would seem improbable.

In the last few years, American films were witnesses to different kinds of excesses, private lifestyle excesses and violence in Zola (2021), excesses in outlandish construction projects, as in The Hummingbird Project (2018), a film directed by a Canadian but in an American context, or then again, an excess or imbalance in our sensory perception, as in The Sound of Metal (2019).

It is possibly to counter these contemporary excesses that recent American films seem to remember more quiet times, as in A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood (2019), or to a period when immigration was not a conflictual topic, as in Minari (2020).

Some films seem to make peace with specific historical or contemporary events, or at least explore them, such as some of the events surrounding September 11, 20021, in The Mauritarian (2021), or the current pandemic in the British film In the Earth (2021).

We will not look here at Canadian films or films from Quebec but will do so in another text.

IN CONCLUDING FOR 2020-2021

Above all, the films of the world of 2020-2021, and generally from recent years, show great continuity. This holds for the films of all continents, even if new themes make their way into cinema, such as films on sexual identity.

Let us look at some examples of continuity.

Films from the Middle East and Latin America still refer to the challenges of collective life and institutions, which then poison private lives. No doubt, these problems are related to regimes and politics, but they also concern the challenges of private interactions.

Films from Central and East-European contexts offer us the opportunity to see that, beyond the successes of integration with Western Europe, there are other, less positive dimensions to that success, in the experience of everyday life. The films out of Russia are very much along those lines.

In comparison, films from Western Europe give us a glimpse of challenges that would seem less immediate or grave, at least for the moment, such as the environmental challenges, excessive consumption of alcohol, demographic imbalance, or the care of senior citizens.

To understand the different themes of different parts of the world, we have suggested the concept of the hierarchy of needs of Abraham Maslow. In less prosperous areas of the world, the films speak to more immediate questions of survival, whether they be political or economic, themes that are less present in more prosperous areas of the world, such as Western Europe.

It will be interesting to look at the themes of films to come in the next several years, as change will occur everywhere, even in a context of continuity.