NOMADLAND

June 13, 2021

This film of fiction, not too far away from being a documentary, takes a kind and affectionate look at what is not frequently portrayed in cinema: the houseless people living in their van in America. Is this a militant film, intending to give us a message about current socio-economic trends in America? Yes, in part. But it is at the same time broader and more specific than that.

Nomadland, a 2020 film of fiction written, directed, and produced by Chinese-born Chloé Zhao, with Frances McDormand, who is co-producer and recipient of the 2021 Oscar for best actress. Based on the novel Surviving America in the Twenty-First**Century, written by American journalist Jessica Bruder. The film also received other Oscars and other nominations and recognitions.

THE STORY

Fern, a recently widowed woman in her sixties, is forced to leave her house and life in Empire, Nevada, when the local gypsum plant closes permanently. Earlier, her husband had died from cancer.

Fern leaves what had been a relatively satisfying life for a very different one, when she decides to live in her van she calls "A-van-guard", 24-7, moving from different locations in the Midwest, going from modest job to modest job, sometimes involving cleaning up parks and trailer parks, sometimes working in restaurants and also, quite often, working in Amazon processing centers.

Life in the different trailer parks she visits is not devoid of social life and even friendships, in a social setting with its own rules and culture. These people can be looked at as "losers", of course, and they sometimes appear as such, complete with the naïve and empty exhortations to "take care" and other more or less meaningless phrases of circumstances.

Fern had developed a friendship with another van dweller, and when he decided to go back to a more standard living style, living with his son's family, Fern is invited to join him in that lifestyle, offer she eventually turns down.

Living from place to place has its charms, freedom among others, but also sunsets in the desert and fireside group conversations and authentic exchanges and reflections. Spirituality also is a regular feature among the dwellers.

THE MOVIE SHRINK'S VIEW

With such a movie and setting, there was a temptation to see the film as a social statement of sorts, as a story about the failure of the American dream and, in the more theoretical language of some social commentators, "a film about end-of-empire and late-stage capitalism". There are, after all, some portions of the film that speak to a harsh reality, where some parts of the American population are cornered into dead-end jobs, and one of the characters in the trailer park gives attention to those realities in speeches on the injustices and human suffering accompanying challenging economic circumstances. But even that character, when confiding about his own circumstances, has to make room for personal, specific elements which may have steered him towards his current life.

In a perceptive comment on the film, New Statesman film critic Nathalie Olah refers to the fact that the film gives space to "contradictions, just as life does". An audience reviewer in Rotten Tomatoes goes much in the same direction, calling the film a "surprisingly balanced view at the van living." There is no one dimension that covers all this film.

Indeed, the film opens the door to different interpretations, with some of them possibly combined. While it is true that the heroine would not have known this nomad life without the local plant closing and while it is also true that Amazon and the likes produce many meaningless jobs, it is also true that Fern would not trade her nomad life without examination of the alternatives.

THE LARGER PICTURE

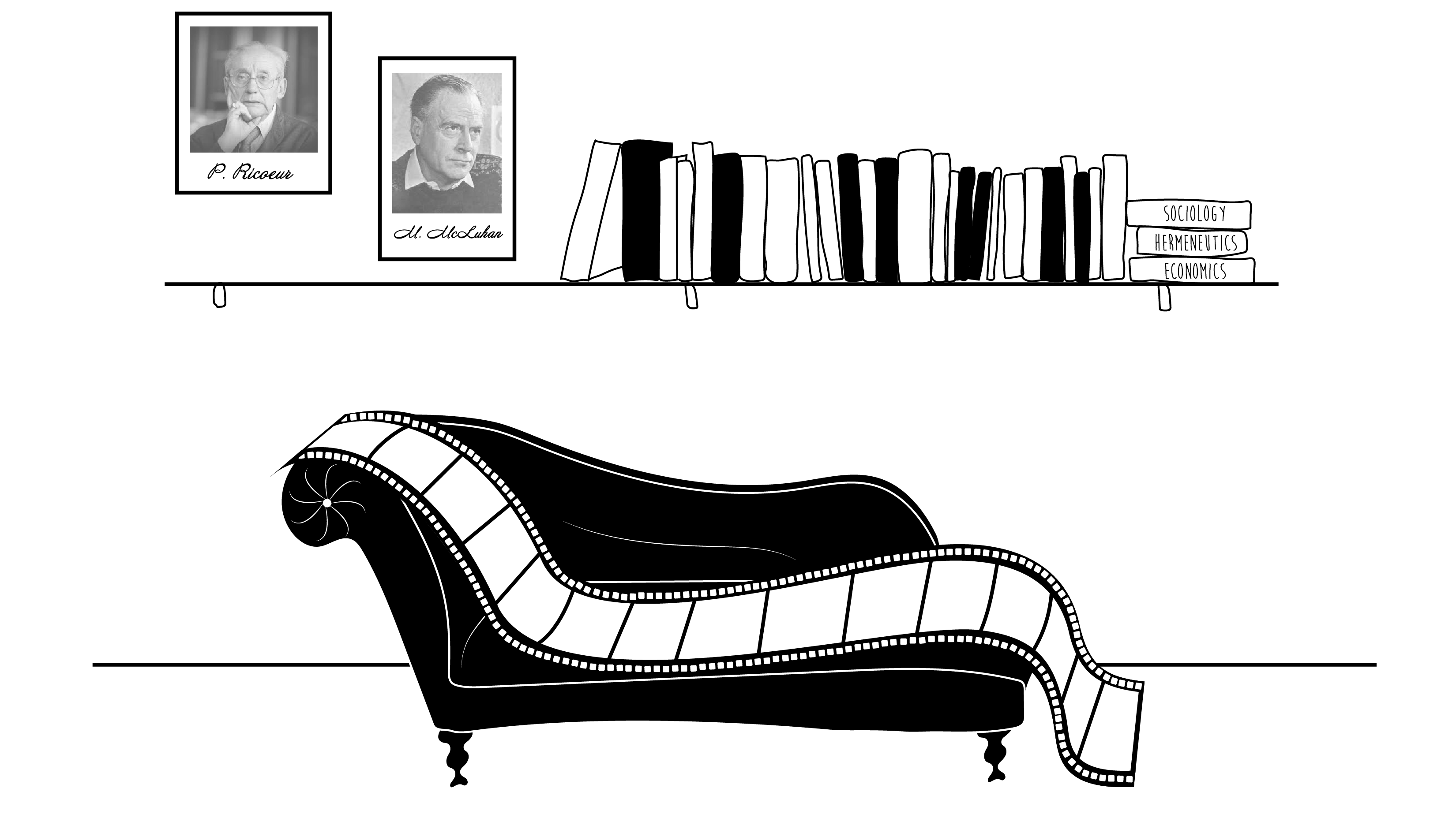

Even accepting that the film cannot be limited to one interpretation, The Movie Shrink always tries to find a common thread, something not obvious at first glance but nevertheless tying the film together, often without the film's creator wanting it or planning it.

Without that, The Movie Shrink's work is not complete.

What ties this film together is the idea of the erosion and eventual disappearance of the sense of place. What is eliminated (or tends to disappear), indeed, is a "specific space", a particular space, eventually a home. Ferns's more or less freely chosen lifestyle, which erases particular spaces, mirrors Amazon's treatment of specific spaces as something irrelevant, just a problem to be solved by standardized transport. Less and less, do we go to a specific local shop or even a specific local shopping mall to gain access to our goods, they come from a largely undisclosed and meaningless place.

An so, Fern's life mirrors the Amazon business: place is ultimately unimportant, or just something to be dealt with, and later altogether eliminated. Between our goods and ourselves, there is no longer a link with a specific space.

At the outset of this film comment, we stated that the film is both more specific and broader than a militant socio-economic comment.

It is more specific because it does not seem to be directed at the whole of the economic system, but only at a part of it, somewhat like the film Sorry we missed you, which looked at the problems related to sub-contracting.

There is something about our currents economic trends that transforms us all, and not only van-dwellers, into nomads.

But the film is also larger and broader because it addresses big and unanswerable questions related to the meaning of life. And life beyond its economic realities.