THE DEAD DON’T DIE

August 10, 2020

A horror movie can be quite significant, beyond its improbable events and systematic violence. This seems to be the case with this zombie movie.

A horror-zombie-fantasy film by Jim Jarmush. United States, 2019.

INTRODUCTION

Predictably, when this film was presented as the opening film of the Cannes film festival of 2019, critics were divided.

Is this film an exercise in style, an essay in a genre, or is there a significance to it, a meaning of sorts? The Movie Shrink believes that it is the latter. Beyond the dozens of heads cut off in the movie, probably a record of sorts, there are underlying elements, tied together, going in a specific direction.

THE STORY

(this is a spoiler alert: do not read this section if you wish to follow the plot only at the screening of the film)

The story unfolds in Centerville, advertised in the entering highway as “a really nice place”. The area, stuck in the sixties culture, with one of the main attractions being a memory lane diner, where a farmer client sports a “Make America White Again” cap, seems to be frozen in time, somewhere in the early sixties. Then, there is Hermit Bob, living in the edge of town, stuck in still earlier times, as he survives by stealing chickens from a local farmer, the one sporting a “Make America White Again” cap. The opening scene has the police chief, Cliff Robertson (Bill Murray), only minimally investigating the latest chicken robbery by Hermit Bob, while recognizing that he will probably not go any further than a timid investigation, leading to the continuation of the status quo.

In some of the early scenes, there seems to be an upheaval of sorts in time or time measurements, with watches malfunctioning and the light of day stretching out unusually into the night. Moreover, televisions and phones are not fully reliable in Centertown. There seems to be a general problem with time.

Young and trendy folks from a large city drive into town in a vintage car, looking down on Centerville, but to their surprise, they learn from the gas station operator that they may know less than he does about film history. The gas attendant also turns out to be a specialist on zombies, something that will become useful later.

At the other end from Hermit Bob, in terms of time zones, as it were, stands Zelda Winston (Tilda Swinton), a mortician expert originally from out of town, practicing serious Yoga in her office, living quite separately from the rest of the city, until she is herself affected by the awakening of the dead in Centerville’s cemetery. At the very end of the film, she will confirm her independence from Centerville, when an outer space vehicle brings her away from the carnage that accompanies the revival of the dead from their graves. The zombies triumph eventually, as police chief Robertson and his assistants are attacked by the growing number of them near the cemetery.

The film presents a comic side to it, with the dry and neutral dialogues of the police chief in the face of dramatic circumstances, as though he and other participants in the story are partly immune to the unfolding drama of aggressive and attacking zombies.

THE SHRINK’S ANALYSIS

What stands out in this film is not so much the zombies and the violence as the fact that Centerville is a contrast in cultural time zones, so to speak. The cars in Centerville present a marked contrast, with hyper contemporary vehicles, like a mini Smart car, an electric car, and even an outer space vehicle, but also a pick-up truck and a nondescript police car, sharing the mobility stage. Yet, overall, Centerville has been left behind the times, with its sixties diner, half- abandoned main street, Hermit Bob, and its advertisement as “A real nice place”. Obviously, the young trendy city folks from out of town do not buy into the city’s spirit and look down upon it, although they may not be so far from it themselves, as they are also eliminated by the zombie attacks. The mortician expert, also from out of town, Zelda Winston, seen as a vaguely European or British born immigrant, definitely stands out as belonging to another cultural zone. Zelda is the only person surviving the zombie attacks, saved by out of earth visitors, obviously coming from a different time zone altogether. The coexistence of people living side by side in different cultural time zones, with of course the zombies still further away than Hermit Bob from contemporary society, since they are literally from the dead, seems to be the unifying element of the film, the underlying element on the screen.

The film can be seen as leading the viewer in other, different interpretive directions. At the beginning of the story, there is a reference to the fact that the upheaval in time, the unlikely sunlight later in the day, and the mal-functioning watches, may be due to the activities of energy seeking petroleum and gas cracking development in the North. This would lead us to an ecological interpretation of the film. Also, in the same vein, Hermit Bob, watching the carnage from his safe vantage point at the edges of the city, comments on the causes of the drama as being caused by the endless search for material objects.

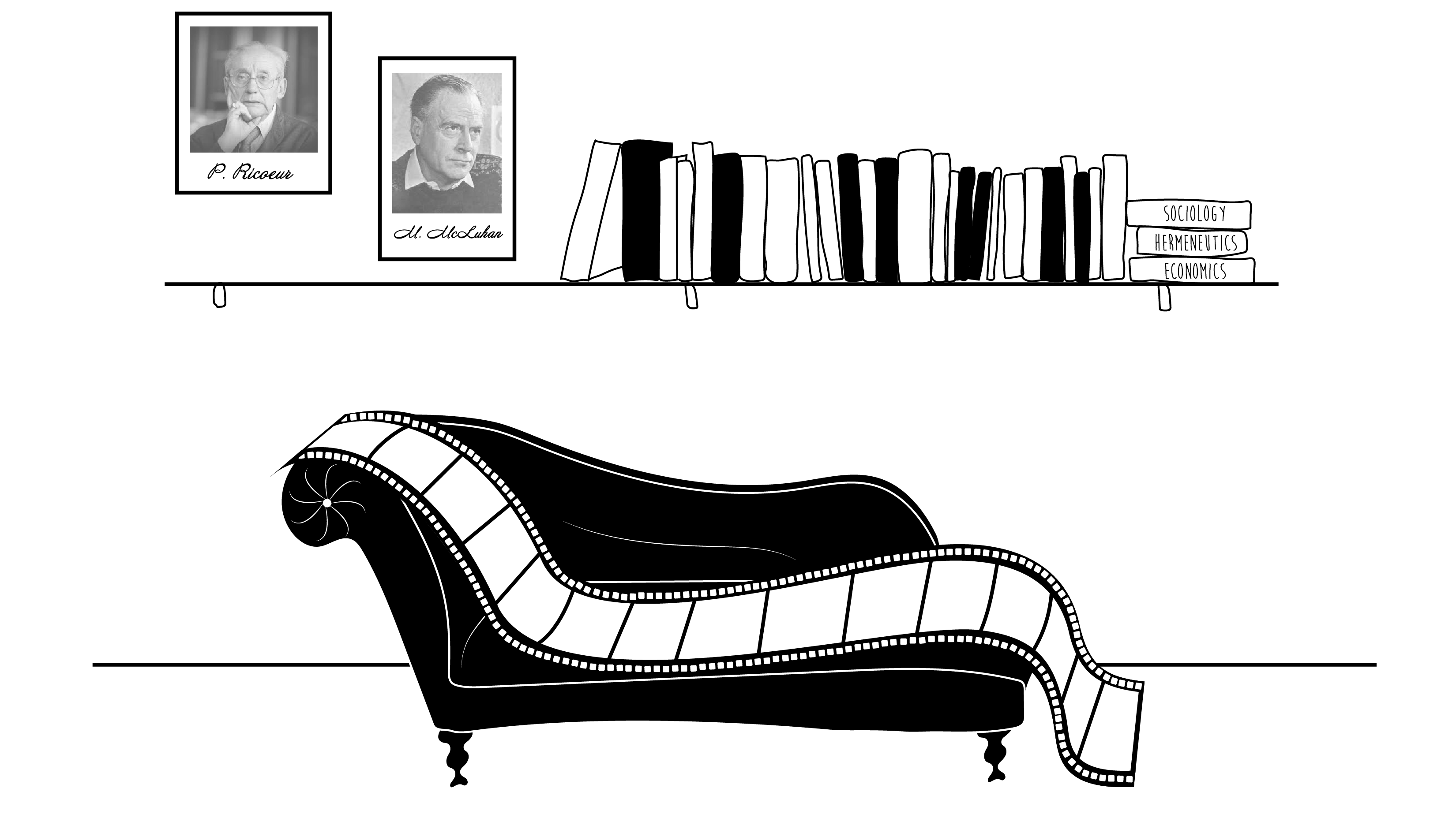

THE BIGGER PICTURE

But those avenues of interpretation only distract us from the conclusion that this is a story about time, and more specifically about humans simultaneously living in different cultural time zones. Like the zombies, places like Centreville, “a really nice place”, survive even though irrelevant and forgotten by changing times and cultures. Because the global village ties us together through our overlapping and ever-present media, we are conscious of these contrasts. The past and the present live side by side, some fully alive, others like zombies.

The world, both inside and outside the United States, is probably full of different kinds of Centervilles, many outdated economically, others culturally, others still politically (the so-called failed states), yet still surviving, like zombies, neither fully dead nor fully alive.

That is the underlying story behind the film.