THERE IS NO EVIL

December 1, 2021

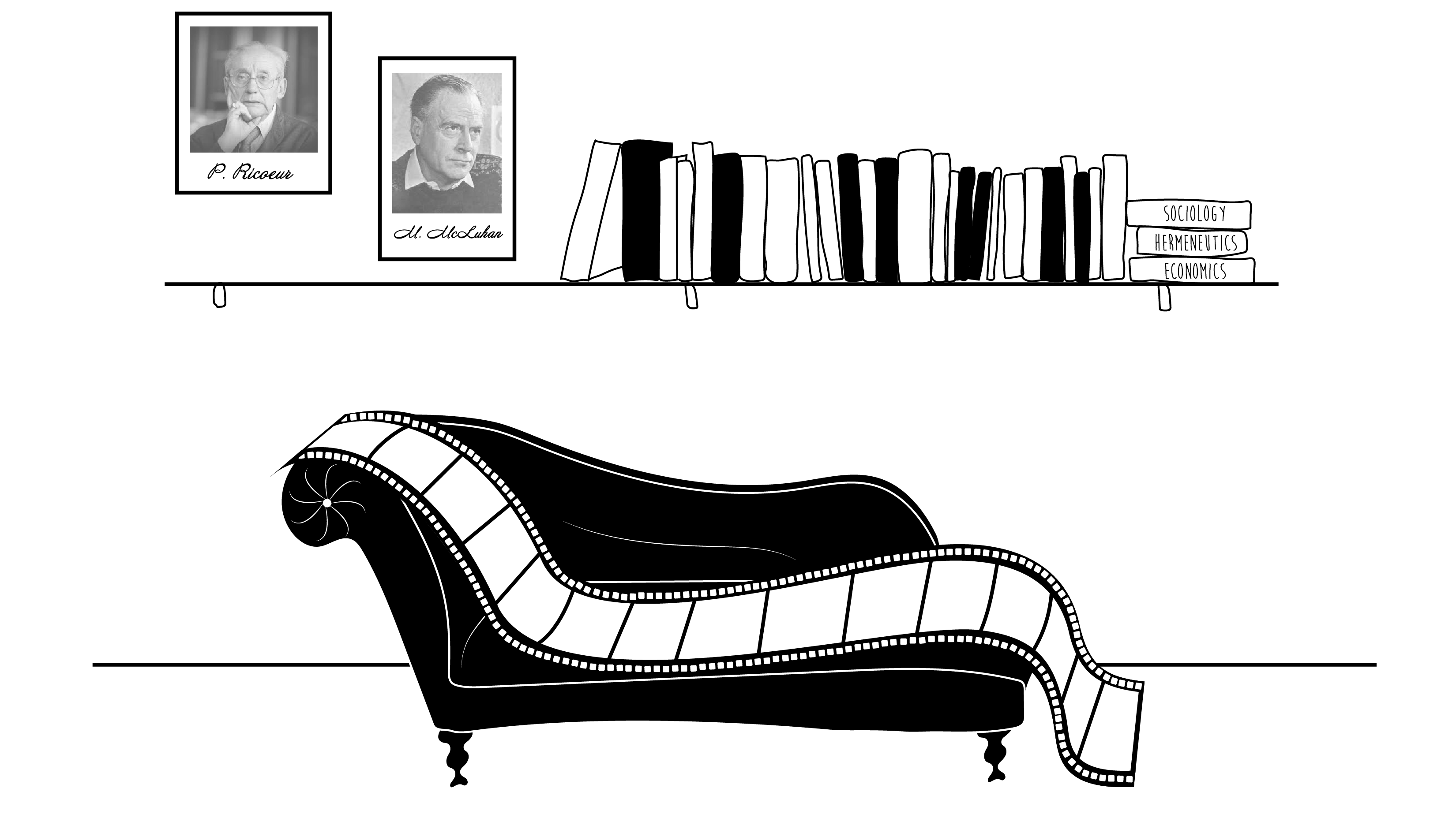

The film may be all the more revealing in that it was filmed in secret, so much its content was sensitive and disturbing. What does this film tell us about Iran that we do not already know, while at the same time being true to a well-established Iranian cinematic tradition?

An Iranian film from Mohammad Rasoulof, available on screens in 2021, and winner of the Golden Bear award at the 2020 Berlinale Film Festival.

THE STORY

We should be speaking more about stories, in effect four stories, that essentially tell of the moral dilemma, often facing young soldiers (three of the four stories) in the context of their compulsory military service, concerning their forced participation in the implementation of death sentences, sometimes involving political opponents to the regime.

Death sentences are still existent and applied in Iran.

The first story is the only one that does not involve a young recruit, but a middle-aged man, good husband, and father, and good and delicate son to his ailing mother, who leaves home for his night shift, which involves pushing a button to have prisoners drop from a stool to their hanging death.

The second story is about a young conscript who refuses to participate in an assigned execution, as he is on duty in the military service charged with those types of duties. In an elaborate plan, which he implements, he frees himself at gunpoint and flees from the military premises, and joins his fiancée in her vehicle, driving to liberty.

The third story tells of another young military, also called upon to participate in an execution, this time clearly involving a political opponent, as we learn later, only to realize afterward that the prisoner was a hero for the family of his fiancée.

The fourth story is about a female medical student, who learns that her real father is a doctor himself, who had lost his right to practice medicine because he had refused, as a young conscript, to participate in the implementation of a death penalty. To protect his daughter, he had hidden the birth to the authorities, by entrusting her to his best friend, who became in effect her father.

SOME INTERPRETATIONS

Predictably, most analysts saw in this film a story of moral and ethical dilemmas concerning individuals, most of them performing their military service, in the context of an authoritarian government. Those are indeed the common elements of the stories that are told.

Robert Abele of the Los Angeles Times writes that the film takes us further by suggesting what it is like to live in contemporary Iran, day-to-day. It is a sign of progress, according to him, from films that, in the past, had criticized the regime only through films “that often relied on child-centric allegory and non-specific narratives to make its societal critiques”.

A LARGER INTERPRETATION

If it is true that Iranian films often shied away from directly criticizing the regime, they have quite directly spoken to the challenges of human relationships between Iranians themselves, whether caused by the political regime or not.

This is the case for several quite recent Iranian films, among them films that received prestigious prizes, such as A Separation (2011) and The Salesman (2016) of acclaimed filmmaker Asghar Farhadi. It must be said, however, that Farhadi tended to the same theme in at least one film that did not refer to Iran, Everybody Knows (2018), this time dealing with rural Spain. These challenges of interpersonal relationships often concern economic relations, related, for example, to contracts or promises to deliver, not always kept, in a conflictual mode. These contractual conflicts are of course present all over the world, and some Iranian films, those from Farhadi in particular, may only be more open in referring to them.

But still, we can look further, concerning the persistence of these themes.

How are these themes related to the larger dynamics of the regime, and to what extent are they societal, related to the civil society? Does religious fervor (or the resistance to it, which would have the same results) intervene in everyday interpersonal and contractual arrangements, with predictable conflicts?

Just as in scientific processes, where definitive conclusions must wait for more studies, we will have to view more Iranian films, recent ones, before pushing this interpretation further.