TITANE

December 1, 2021

This film which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival of 2021, the supreme honor of the prestigious meeting, leaves no one indifferent. Its viewing can cause a sense of discomfort. Does its violence and unlikely story have any overall meaning at all, or should we simply refrain from such a quest, as seems to sometimes suggests its director?

French drama, with horror overtones, from filmmaker Julia Ducournau, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2021, among praise, but also opposition, from viewers.

THE STORY

It is the story of a female murderer who is also mysteriously and dangerously pregnant from intercourse with … an automobile. To avoid police, looking for her, she takes on the appearance of a missing youngster, changing her apparent genre in the process, in effect becoming a boy. She presents herself as such to the grieving father of the missing boy, only too happy to think he has found his lost son. In several most bizarre developments, the two participants in the scheme, the fleeing heroine and the happy father, both with their own reason for believing the reunification, become closer as the moment of birth approaches for the future mother. Not to mention the seeping oil that bleeds from the pregnant mother to be, presumably replacing the bleeding of blood sometimes present in those circumstances.

TO UNDERSTAND… OR NOT TO UNDERSTAND?

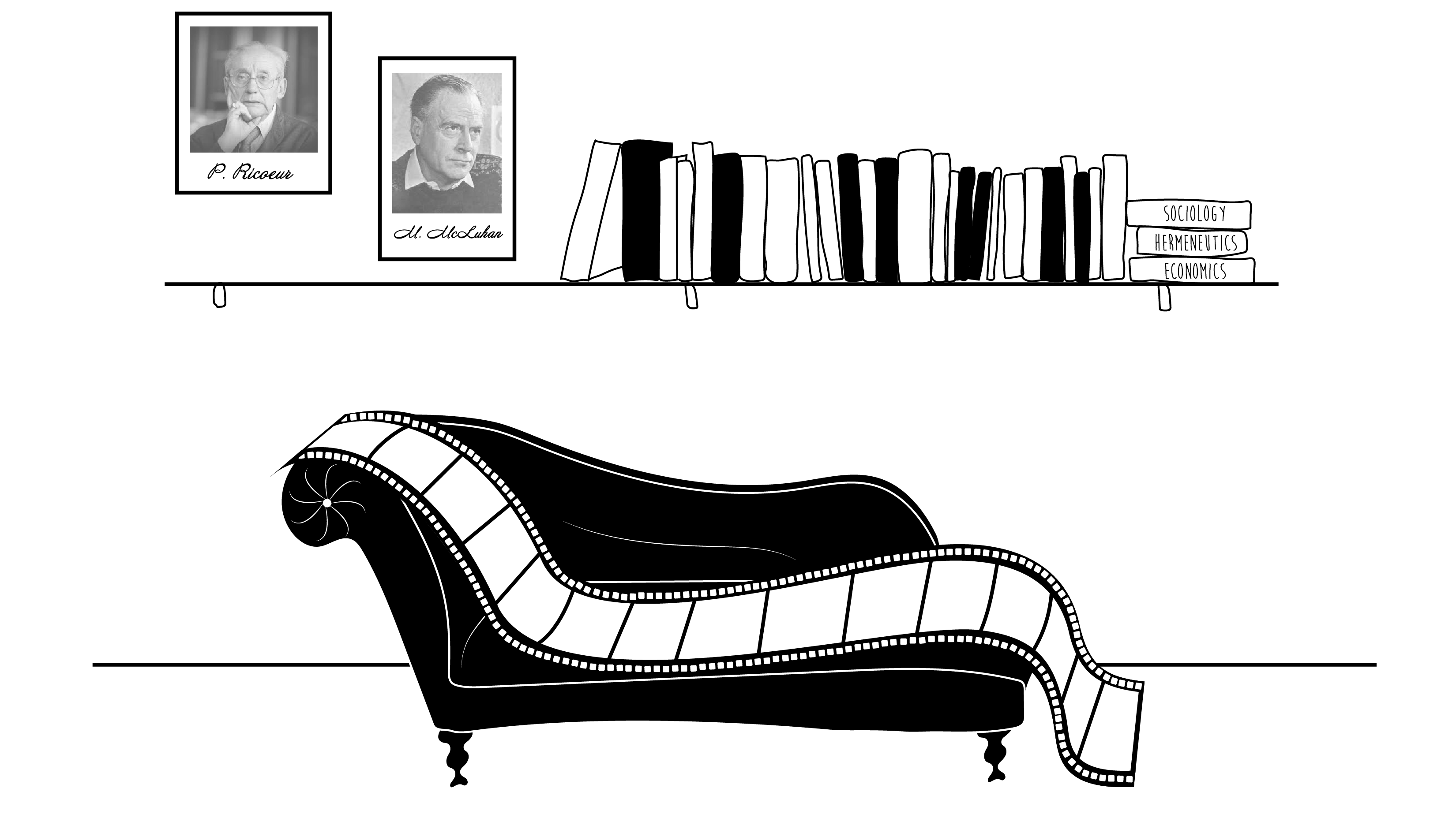

We can quietly renounce to finding a sense, a meaning, to this film. Several film experts will say that trying to find meaning to such a film simply shows an unsophisticated and quite passé cinema culture. Still, what is happening today to make such a story invented at all?

Mark Feeny, of The Boston Globe, asks: “Does (this film) make sense? No”, he writes. Cody Corral of The Chicago Reader goes in much the same direction: “Titane will not give you the answers to your questions”, he concludes.

For Marc-André Lussier, of Montreal’s La Presse, the film is a film de genre, which probably dispenses it from making sense, at least in a conventional way. We could add that we could look at it as an aesthetic piece, as an artistic creation, much as we would look at a painting from Picasso, not trying to find a linear and constraining sense to it, even though some paintings of Picasso, such as Guernica (1937) can refer to an effort at showing the cruelty of war and conflict.

In some interviews, the film’s director, Julia Ducournau, seems uneasy with the search to find meaning to the film, adding that the film, once produced, “has a life of its own”, an autonomous and independent life. Is her statement a coquetry of sorts, the addition of a mysterious quality to the film, which would make it still more interesting?

STILL, TRYING TO MAKE SENSE

Still, even with all these qualifications, we can still try to find something about this film that somehow speaks to our times.

Marc-André Lussier may be showing us a path in suggesting that the film may be precisely about deconstructing categories. In other words, the film may have a cognitive dimension to it, an effort to shake our mental categories and schemas. it would be an unproductive quest to try to understand it through the categories it is precisely trying to negate.

Still, could there be an additional dimension to the film, a more conventional dimension, which could be intertwined with the cognitive challenge?

In a period when it is sometimes said that our mental and cognitive categories are related to structures of power, could it be that to challenge them entails a more standard pattern of power and struggles? Who has an interest, in the more traditional sense, in shaking our mental and cognitive categories?

Since the film does not seem to advance an agenda of economic struggle, there remain other potential struggles as candidates. A feminist dimension can not be excluded, even though the film’s creator does not encourage such an interpretation. The first part of the film does present a pregnancy coming from intercourse with a car, not a male, at least not a male in the usual sense. And the second part of the story is about an apparent change of genre, with a female becoming a young boy.

This interpretation could be seen as unlikely and abusive. But to hold that such a film does not speak to anything about our society, or our times, could also be argued as unlikely or abusive. The filmmaker’s wish that we do not see in her film too many standard categories should not prevent those looking at the film’s, viewers and analysts, to make sense of the story. We are not limited by the filmmaker’s preference. We are all moved by patterns and processes we are not fully conscious of, artists included.

P.S The fact that several recent films from Europe have as central themes the death or disappearance of young children (in addition to Titane, we can mention Koko-Di Koko- Da, Lamb, and My Zoe) is not altogether clear for the moment but may be significant.