MORE ON HERMENEUTICS

Hermeneutics is involved in the study and art of interpreting. The origins of the word “hermeneutic” are somewhat disputed, and sometimes its origins are associated with the role of Hermes, the Greek messenger of the gods, bringing messages to humans.

Hermeneutics has been concerned at the very outset, and still are today, with the deciphering of challenging or unclear texts.

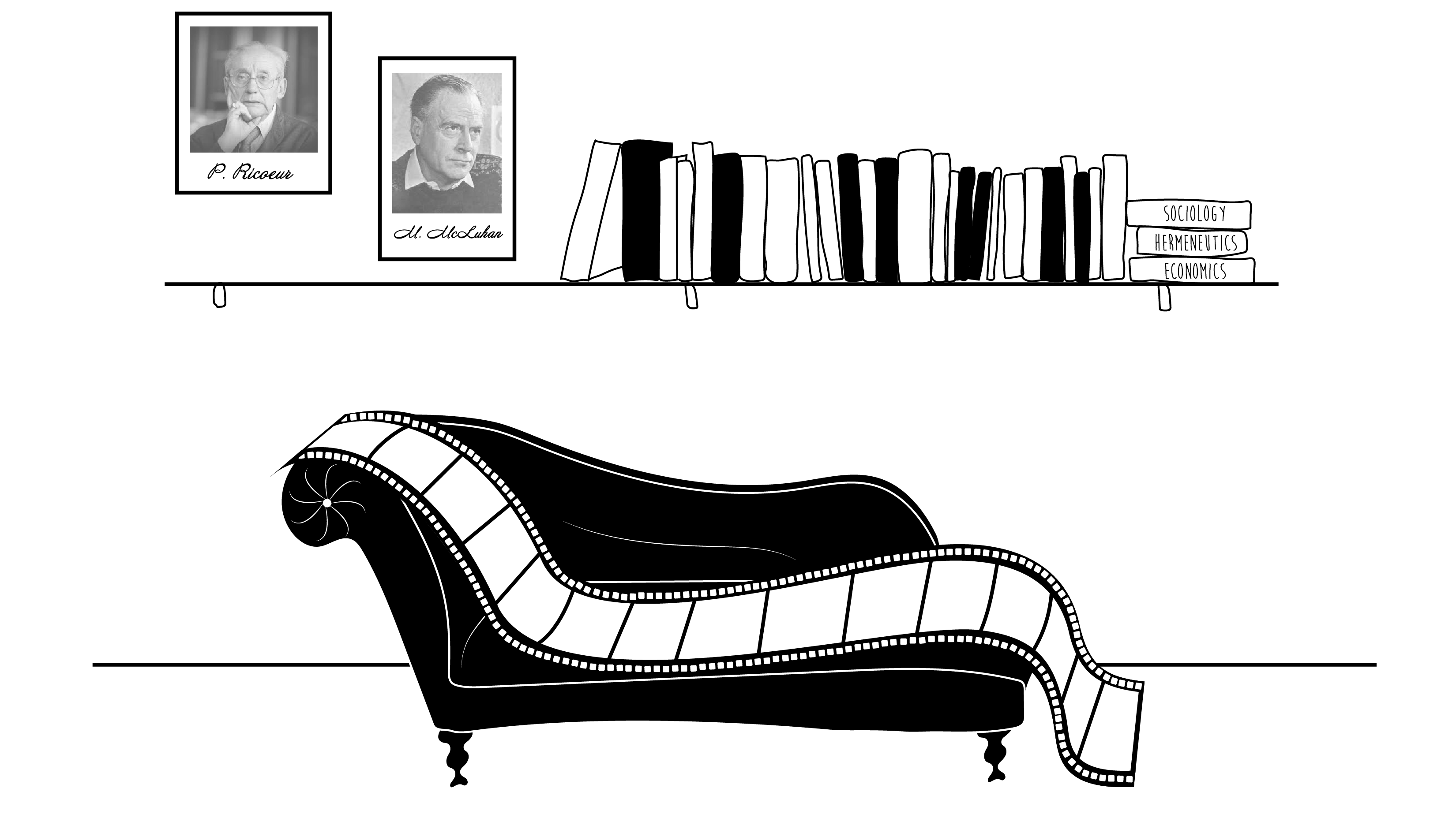

And so, at first, hermeneutics has been involved, above all and almost exclusively, with written texts, most often religious or legal texts. But French hermeneutic philosopher Paul Ricoeur extended hermeneutics' domain to “text like” creations or human productions, which includes, for example, architecture, paintings, and most of the artistic expressions, including, in our case, films and cinema.

Now let us move deeper into understanding films through the use of hermeneutics.

Let us look, more specifically, at how the need to better understand challenging and significant films leads us to hermeneutics.

In a sense, all films speak about the human story but, on this site, we want to concentrate on some of those films that appear to us as particularly significant in this regard.

Among those numerous films that speak to us in a significant way, we want to concentrate on those films where part of the content is presented somewhat indirectly and needs to be deciphered, beyond our immediate understanding. The story that is told in the film has some quite explicit aspects, while, at the same time, leaving some important elements understated or implicit. These implicit but important aspects become, as it were, The Movie Shrink's basic material, and they are not as much hidden as they are in need of interpretation, in need of additional work for the spectator. Such is the hermeneutic approach to understanding significant films.

The additional work required for the spectator, or the analyst, is often to find a common thread in the story, a common thread that is not explicit at the outset. The additional understanding sheds light on the story, often by tying together elements that seem, at first glance, unrelated. Finding a significant unity in certain films, beyond their first reading, is the task we want to respond to in this film site. Then, an effort is made to tie this understated meaning to contemporary society and the human story, as it unfolds in the twenty-first century.

THE MOVIE SHRINK'S TOOLBOX

While being attentive to the risk of too much interpretation, taken too far, we nevertheless think that artistic creation has something to say to us about the human experience, beyond its aesthetic dimension, as suggested earlier. German philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer, a specialist on hermeneutics, had criticized in his long and distinguished career the tendency to see art as only a question of aesthetics. Art is, according to Gadamer, also a source of knowledge about society, more specifically about the contemporary human experience. As an artist, the filmmaker himself does not always plan to present this knowledge deliberately, as we suggested earlier. That is not a problem, quite the opposite, because there is a certain degree of unconsciousness in all artistic creation. The role of the hermeneutic process, on the other hand, is to bring to a greater level of consciousness this meaning when this meaning is difficult to identify.

There is no need for the application of the hermeneutic method when, at one end of a continuum, the meaning is clear, or when, at the other end of the continuum, there is an overabundance of overcharged symbols and metaphors, going in all directions, obscuring the content of the film under study.

There are other foundational elements that make up The Movie Shrink's toolbox.

We referred earlier to the contribution of French hermeneutic philosopher Paul Ricoeur, and specifically to his suggestion that we include in the hermeneutic work “text like” creations, which opened the door to consider films and cinema as objects of hermeneutic interpretation.

There is another important contribution from Paul Ricoeur that is pertinent for our purposes here.

It concerns Ricoeurs's idea that, when interpreting a text or a text like element under scrutiny, we often do not start with a completely clean slate. Sometimes, maybe most of the time, we have an idea of what we are trying to find, a sort of preliminary understanding of what we are looking for. He calls this preunderstanding the hermeneutics of “suspicion”, as opposed to the case when we look at something with a completely open mind, which he calls the hermeneutics of “openness”.

The hermeneutics of suspicion, as a starting point, is neither worse nor better than the hermeneutics of openness, they are only different. The preunderstanding of the hermeneutics of suspicion is not necessarily problematic since our preliminary understanding can be useful if kept in check and abandoned when it proves false or misleading. Many other hermeneutic philosophers have given attention to this process of preunderstanding, and Gadamer and his teacher, Martin Heidegger, have pointed out that this process is unavoidable and must be recognized.

In this spirit, we want to make explicit some of the basic elements that constitute our own preunderstanding of the films we look at in this commentary site on cinema. These elements are, as it were, The Movie Shrink's toolbox.

First, it must be said that the author of this site comes from what is called the humanities and the social sciences, more specifically from political science, sociology, and economics. In the preunderstanding of the films we choose to look at, we indeed believe that the film cannot escape the context of the times in which it is created. It can only reflect the times that give birth to its creation, whether the film portrays the present, the past or the future. More specifically, a film reveals something of the socio-economic context in which it appears. All through the twentieth century, and beyond, the history of cinema, starting at the same time as the twentieth century itself, was witness to all manner of historic, social and economic changes, reflecting, among other changes, the greater reach of our communication media and the growing size and scale of human organizations, from village, to growing city, to nations, and globalization, and possibly moving to smaller scale again. These elements are large scale and moving slowly. They are, in a sense, the elephants behind the screen. We can sometimes get a glimpse of these movements in works of art or films.

When looking at the films we choose to spend time on, which are not chosen randomly, of course, we are mindful of these socio-economic dynamics, not to judge them or take positions on them, but only to better describe them and understand them.

Ideally, the story that the film tells is related to the evolving human story of where we are, as humans, at this time in history. Films can be seen as chapters in the human story.

In trying to understand these socio-economic and historic aspects, we rely on some specific disciplines that, together, make up the elements of our preunderstanding and our hermeneutics of suspicion.

Drawing from sociology, we are guided by some aspects of its interpretative (or interpretive) and historical tradition, found among others in the work of Max Weber. In economics, we are mostly interested in Institutional economics (sometimes referred to as New institutional economics) a school very much interested in the changes brought by evolving patterns of human and economic interactions. Finally, from a media history point of view, the work of Canadian media philosopher Marshall McLuhan (« the global village » and « the medium is the message ») is for us an important source of understanding.

These elements and authors can be seen as constituting an important part of The Movie Shrink's toolbox, in addition to hermeneutics. As stated earlier, it is in keeping with many hermeneutic analyses to recognize that there is a kind of pre-understanding, possibly abandoned later, in any effort at understanding. We have just exposed some elements of our pre-understanding in referring to Max Weber, to Interpretative sociology, Institutional economics, and McLuhan theories on the history of media.

There are other sources for understanding films on this site, but the ones just mentioned can be considered as the principal ones.